Egg-zactly What Are You Paying For?

Peeling away the marketing stories to get to the core truth for hens and farmers.

The Federal Trade Commission’s opposition to the merger of the two retail grocery giants Kroger and Albertsons has dominated the food news over the past month. The FTC is concerned about the merger reducing competition in many local grocery markets and increasing grocery inflation. The FTC’s investigation revealed an email from Kroger’s senior director of pricing saying that “retail inflation on essential items…” including eggs and milk has been “considerably higher than cost inflation.”

For decades, egg price increases lagged general inflation. But lately, egg prices have been rising faster than general inflation. The price of eggs in the grocery store is now going up faster than the cost of producing eggs is. Consumer demand for eggs is “inelastic,” which is a fancy way of saying that we complain about the prices, but we keep buying them. This makes eggs a good item to start price gouging, if you are so inclined. My research shows that the late-2022 price of eggs was (just barely) the highest in almost fifty years. After a brief dip in 2023, egg prices have increased again in 2024. Yet, egg-production input costs have been decreasing in 2023 and 2024.

Eggs price inflation, 1935→2024 (in2013dollars.com)

This news sent me circling back to an investigation into grocery-store egg prices and quality that I started last winter, before I got so interested in how eggs get to our respective tables, egg farmers, and hen health that you’ve seen from me over the past few months.

Readers have asked me what a conscientious egg-consumer can choose in the grocery store to help farmers as well as their own health. Some of you have also asked me about nutritional variations and yolk color, having noticed differences between brands and over time. Many of you have asked how to use their grocery dollars to influence the care of the hens laying those eggs. So, let’s crack a few eggs together – and crack a few egg-marketing stories!

Last winter, one of you asked specifically about the brand Vital Farms featured in an up-scale organic market as “pasture-raised.” To tell the truth, I hadn’t noticed the Vital Farms (VF) brand because I hadn’t been shopping for eggs at grocery stores for a while. The timing of this question was good, as my neighbor’s flock size had been challenged by the local foxes and the remaining hens had packed it in for the winter. I was running out of the eggs I had frozen and pickled. So, I headed out on a grocery expedition and egg comparison journey. At my local Food Lion (FL) last Christmas, I was surprised to find that the store’s efforts to move upscale a little included introducing Vital Farms and some other upscale brands. It seems that I might not have to go all the way to Whole Foods to find Vital Farms eggs:

Food Lion did not stock the organic “restorative” eggs – you have to go to a specialty organic market to find those. Really, $10.99 for a one dozen eggs boggled my imagination. “Restorative” was a new term to me in this context, so I looked for a definition. There’s a lot of hand-waving in the food production community, but no agreement on its meaning. It seems to be the newest marketing term for “regenerative,” possibly applied when regenerative techniques have just been introduced to a farm. I have a bit of a beef about the term regenerative being new, as it looks a lot like the no-till Dad introduced in our area in 1970. We called it “sod-planting” then. I will dig deeper into this whole regenerative story in the future, but the idea is practices that improve soil health and soil organic (carbon) content and prevent erosion. Turns out that no one knows exactly what regenerative practices are in egg production, any more than they know what restorative practices are. Currently, no one offers a “regenerative” or “restorative” poultry practice certification. For now, VF seems to be using “restorative” as a kind of placeholder for attempts at using chickens to promote “sustainability.” The Vital Farms videos that I checked out did not show “pasture” meeting my definition of regenerative practices, but those videos showed only the $6.99/dozen farms.

The expenses of transitioning my new farm from hogs to vegetables made paying $10.99 for a dozen eggs feel too extravagant, especially without a good definition of what the extra $4 was paying for. I went back to my local Food Lion and bought a dozen each of Vital Farms (VF) Pasture-Raised Hens eggs ($6.99) and Food Lion (FL) store-brand eggs ($2.39) to compare.

The VF eggs were a rich brown, and very pretty. But looks are not everything, so I started my comparison with Mom’s old float test (What Color was the First Chicken Egg? - by Kristin Farry (someonegrewthat.farm)). This test showed that the Vital Farms eggs were not quite as fresh as the Food Lion eggs--the VF egg was starting to tip up. The VF egg carton had a sell by date of 1/11/24 while the FL egg carton showed 2/4/24. Hmmm. I think I just learned that Food Lion sells low-priced eggs faster than high-priced eggs, rather than VF having some systemic freshness problem. You might want to check those sell-by dates on any eggs you buy, but most especially the high-end ones at stores where people like me shop.

Vital Farms allows you to trace your eggs back to the source at the dozen-egg batch level. This impressed me until I remembered that the European Union tracks individual eggs ((10) What Color was the First Chicken Egg? - by Kristin Farry (someonegrewthat.farm)). Still, it’s fun – and a positive step toward accountability.

VF claims to have 300+ “small” family farmers as partners. But how does VF define “small?” The USDA defines farm size in terms of farmer gross income, not land size. I looked at the application to become a Vital Farms egg producer. They are only asking for “family farmers” not “small family farmers.” They currently require a minimum of 52 acres of suitable pasture for a minimum of 20,000 hens per farm. A typical laying hen can produce an egg every 26 hours. Because daylight influences her ovulation, she’s probably going to skip one day per week. That’s over 18,000 eggs per day, and a half-million eggs per month from the smallest VF egg producer. And over 46,000 dozen eggs per month. This does not sound “small” to me; however, the USDA says that about 81% of egg-producers have flocks of 30,000 hens or more. With the average American eating about 280 eggs per year now, one 30,000 hen flock keeps over 30,000 Americans in eggs all year.

So VF’s minimum flock size of 20,000 hens is smaller than the average USDA-reported flock sizes, but VF does not disclose their average flock size on the public website. Applying a little math to the VF minimum flock numbers suggests their average space per hen could be as much as 113 square feet per hen. That’s a little more than their stated minimum of 108 sq ft per hen, which is also the minimum required in the “certified humane” rules for “pasture-raised” poultry. Good!

According to the Certified Humane Animal Care Standards, Version 21 for Egg-Laying Hens, the label “Pasture-Raised” requires year-round pasture access, at least 6 hours per day during daylight hours. Emergency confinement indoors is limited to 14 consecutive days. If you are located where the daytime temperature gets below freezing and precipitation (eg, snow) can prevent free movement of the birds outside, but you still provide the birds with 108 square feet per bird outside on the nice days, you can apply for the “Seasonal Pasture-Raised” certification. My farm is outside of what VF considers the “pasture belt,” the region where poultry can be outdoors year-round, and so is not eligible for a partnership with them. I am wondering if I should research that “seasonal pasture-raised” certification.

Contrast 108 square feet of “pasture” per hen with only 2 square feet of “outdoor space” per hen for the “Free-Range” humane certification. Note that the basic “Cage-Free” humane certification requires at least 1.2 to 1.5 square feet (indoor or outdoor space) per hen. There’s a lot more to the humane certification and even the space in the 45-page standard, but this is a key difference between the certifications. The “Free Range” certification space requirement of 2 square feet was a surprise to me. My mental picture of “free range” had birds strolling around everywhere on the farm, more like the pasture-raised standard, not in small outdoor pens. Nope. It can mean a concrete-floored, covered area that differs from the rest of the hen-house only in its absence of solid walls.

The dozen VF eggs I bought came from Rusty Feather Farm. It’s fun to scan the end of the carton and download a video of the hens. They have red (rust-colored) hens on this farm, which fits the “Rusty Feather” moniker. The video shows them flocking together in a large field. I would not call that field “pasture.” There are very few green plants. And those plants are not grass, just some stalky plant species. Where I come from, that’s a “lot,” not a pasture. VF’s farmer-facing page suggests that pasturing poultry is a good use of “marginal land.” Reviews of many VF farm videos show a lot of woodland in use for “pasturing” these flocks – grass doesn’t grow in heavily-shaded areas. This bare ground does not meet the “Certified Humane Pasture-Raised” standard, which requires maintaining actual grazing conditions. This is also not “regenerative agriculture” practice by any definition of that term that I have found. So, VF gets points from me for transparency but not for meeting all the Humane Pasture-Raised standards. Perhaps the hens producing the “restorative” eggs ($10.99/dozen instead of the $6.99/dozen these cost me) have a real pasture and that increases their production cost?

The chickens at Rusty Feather do seem happy, however. In the video, they are enthusiastically gathering to peck at the dirt and clucking a lot more than a grazing hen usually clucks. My guess is that they are enjoying a snack scattered on the ground to encourage them to come to the camera. Some buildings in the background are likely laying areas and nighttime roosting where Mr. and Ms. Coyote can’t snack on the hens or their eggs.

The VF website caveats the pasture access with a note that a health emergency may require the hens to be occasionally confined indoors – hence the 14-consecutive-day confinement exceptions in the certified humane standard. In other words, when the avian flu threat is high, your VF “pasture-raised” eggs are really “cage-free” eggs. I suspect that their prohibition on ponds and creeks in the pasture in their farm requirements are related to the fact that migrating waterfowl have been a major avian flu transmission vector. Folks, protecting your flock from disease is not cruel, even if it reduces their freedom to roam. Just keep this in mind while buying eggs from the grocery store during chicken health emergencies—there may zero difference between how the hens are treated and fed during these emergencies, no matter what the carton says.

VF’s marketing department doesn’t call the birds “hens” on the website. They call them “girls.” Even the VF CEO talks about the “girls” when interviewed by business magazines. That’s the sort of term a farmer uses. We called the brood cows and the ewes on our farm “The Girls.” I greet my neighbors’ hens with “Hello, Ladies” or “Hello, Girls” when I raid the nest box for eggs and drop off my little feed supplement thank-you. But “Girls” seems a little over the top on a marketing website. It feels like co-opting, to be honest. I find myself wondering, “How much poop have YOU scooped? How many nights have YOU spent in a barn lately?”

The bare ground in the farm videos on the VF website is quite a contrast with the website banner photos. The website banners show hens walking through tall, diverse grass. It’s also a contrast with the FAQ on what the “girls” are eating. Here are some quotes (in bold text) with my reaction:

“seeking out native and seasonal grasses like clover, rye, and wild onion.” Um, when did clover and wild onion get re-classified as “grasses?” And when did clover get re-classified as native? It’s a European import. The VF marketing department is not filled with grass farmers who have spent decades grazing livestock.

“They don’t stop with plants, though! You’ll often catch our girls munching on a grasshopper or snacking on a worm.” Hmmmm…. No grasshoppers without grass, folks.

“supplemental feed consists primarily of corn and unprocessed soybean meal, which the hens need for protein, as well as additional natural ingredients, including paprika and marigold, which, along with their outdoor snacks, provide nutrients and help the hens produce eggs with deep orange yolks that our consumers prefer.” VF hens are essentially eating the same grain diet that FL hens are eating, with an additive to fake the appearance of a more natural diet. Their “outdoor snacks” are apparently too rare to make yolks look that natural-diet orange. I also have to question the “unprocessed soybean meal” part. Raw unprocessed soybeans can irritate their intestinal tracts and interfere with protein digestion and mineral absorption. Raw soybeans inhibit growth of chicks, too. Feeding additives to counter the negatives of feeding raw soybeans is still on-going. For now, if you want to make soybeans more than a token feed additive, you need to roast them to make them safe for your hens. This is true for mammals without rumens as well as poultry. And of course, you need to grind them. Roasting and grinding soybeans sounds a lot like “processing” to me.

In my skillet, VF egg yolks were bright orange from the paprika and marigolds. I can’t explain why the VF yolk was a smaller percentage of the egg volume that the FL yolk -- genetics, perhaps? The FL egg white less was transparent than the VF, but that just confirmed that the FL egg was fresher than the VF egg, rather than being a comment on the feed or quality.

What was I expecting to see in this skillet? Chickens are naturally omnivores. They eat anything they can outrun and they can get a beak around. In practice, this is usually plants and insects, but even the odd baby snake is dinner. An egg from a hen with a lot of plants and insects in its diet looks different in the skillet from one raised with grain.

Last fall, I had a nice review of how the differences in hen diet show up in the skillet. My main source of eggs for a couple of years was my neighbors’ backyard flock. For over a year, their hens were out every day, all day, eating bugs and plants all day and topping off in the evenings with a “egg-layer” grain-based ration from the local feed store. They’d stroll into my front door if I left it open or hop into my truck while I was unloading it. Then a coyote and a fox family moved into the area, and some of the hens became their dinner. The remaining hens are now “free ranging” in their hen-house 24/7 with its small enclosed run, eating only a grain-based ration. Same hens, different diet. The difference is quite noticeable in the skillet. My neighbors’ eggs currently look just like the Food Lion eggs (although fresher, with thicker, milkier egg whites). Last year’s eggs had even thicker whites, and the yolks sat well on top of the whites. The yolks were darker and more orange than the current eggs, but not the bright orange of the Vital Farms eggs. No marigolds or paprika in their diet. In my way of thinking, marigolds are what you plant with the tomatoes to keep the bugs away, and paprika is what you use to season eggs (especially huevos rancheros), not food for the hens. I can’t imagine a hen choosing to eat paprika when there are green plants and insects, even dung beetles, to eat. Some people run chickens with their livestock just for parasite control, never mind eggs. I wanted to try that, but over the years, we did too good a job of wildlife restoration on Excalibur, and chickens ranged with livestock would have become coyote lunch in very short order.

I suspect that VF pays their marketing gurus more than they pay their farmers. The vitalfarms.com website includes banners like “Raised with Respect” and “American Family Farms,” “Conscious Capitalism,” and “Honest Food, Ethically-Produced, No Bullsh*t.” Their website contrasts their “pasture” practice with “cage-free” operations, claiming that those average 1.8 sq ft of space per hen, just unconstrained. They have an entertaining little video of the human-office equivalent of “cage-free” which is misleading. Yes, the “cage-free” hens have an average of that much space, but they are in a large open space. The office cubicle analogy would be a more appropriate analogy for caged hens, not cage-free. Think of a big open office bay instead of office cubicles for the cage-free analogy. Still, creative advertising aside, we have to give Vital Farms credit for giving their hens roaming room when conditions permit it. As for “American Family Farms,” the US exported 23 eggs for every egg imported last year, so even though Food Lion is a Belgian company, the basic Food Lion eggs are most likely also “American.” I don’t know about the “Family Farms” part as a marketing tool. What’s the definition of “family?” Since I became a solo farm owner recently, can I still represent anything I grow as coming from a “family farm?”

Slick marketing trying to push my buttons to make me open my wallet wider tends to annoy me; however, I had bigger concerns. What is the relationship between Vital Farms and the farmers? Recall that my turkey newsletters last winter dug into the vertical integration for poultry. The dominant arrangement in “broiler poultry” has the farmer-grower providing only the facility to house the birds and the labor while the processor provides the chicks, feed, and veterinary care; the grower never owns the birds. A completely vertical integration where the processor owns the facilities and pays wages to laborers to take care of the birds is more common in turkeys than broiler chickens.

Unfortunately, as you’ll recall from my earlier post, complete vertical integration dominates the table-egg industry ((10) The Chicken or the Egg? - by Kristin Farry (someonegrewthat.farm)). Vital Farms is somewhat less vertically-integrated. They describe their business model as an enhanced “middleman.” VF handles contracts with a large hatchery to get the young, ready-to-start-laying hens (called pullets) on the farmers’ behalf. Their farmers buy the hens and own them during their laying phase. VF enters a multi-year contract with their farmer “partners” to purchase all their eggs. Note their use of the word “partner” instead of the label “grower” common elsewhere in the industry. The farmer must build a facility to VF’s specifications, getting their own financing independent of VF, in order to “partner” with VF. VF dictates care and feed composition (while requiring the farmer to purchase VF feed). VF arranges shipping of the eggs from farms to their processing facility “Egg Central Station.” And the difference between this “partner” and the “grower” is…? According to VF, it’s the farmers’ ownership of the birds while they are laying, versus other industry players retaining ownership of the birds even while they are on a farm and laying.

I find myself wondering if “farmer ownership” of the hens in the VF contracts is a cover for VF externalizing more risk onto the farmer, because the farmer has given up the freedom to make any of the care decisions. The VF website encourages the consumer to ask questions of the farmer producing their dozen eggs, so I tried asking the farmer about this. Turns out that VF corporate screens communications submitted via their website invitation to “ask the farmer” questions. A VF corporate employee intercepted questions I had directed to the Rusty Feather farmer. Their corporate answer was basically “apply to become a VF farmer to get the details of our relationship with farmer-partners.”

So, I started the application process for my new farm. The VF application for farmers is almost the same as for more vertically-integrated corporations, except for some additional questions about pasture availability and why you want to grow for Vital Farms and your “farm philosophy.” VF is not sharing their contract with anyone who doesn’t have at least 52 acres available in the “pastured poultry” climate belt, so I couldn’t get far enough in the process to learn how risks are shared between VF and its farmer-partners. Ah, the irony of having a farm too small to qualify as “small” for an egg producer.

I suppose it’s fair to treat contract conditions as proprietary. I looked elsewhere, at general industry and open-source information, to see what costs and risks VF pushes onto the farmer beyond the farm and facility. What happens if a disease or other disaster strikes a VF partner flock: does the farmer bear 100% of the loss? Or does VF assume some of that risk? It depends on the disease or disaster. The US Department of Agriculture pays poultry producers for birds that are “culled” when avian flu is detected on their farms. In 2023, this reimbursement totaled over $500 million dollars. The USDA pays this bill to encourage farms to report the infection of their flocks. The USDA also now offers poultry producers assistance to upgrade their facilities’ biosecurity (government-speak for measures to prevent disease spread).

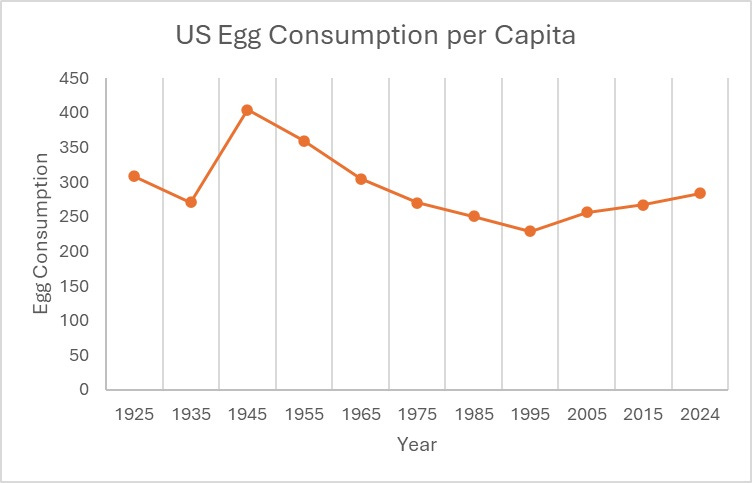

These USDA programs make me wonder why the 2022 grocery-store egg cost increase was blamed on avian flu. The price increase is not driven by the cost of replacing the culled chickens because your tax dollars are paying for those. The flu impact is only an interruption in supply while hatcheries restock hen houses, and the hens mature to laying age (about six months from egg hatching a chick to hen laying eggs). This impact shows up in total US egg production and in US egg consumption per person, along with pandemic supply chain problems.

Take another look at 2014-2015 in the chart of egg prices corrected for inflation. That avian flu outbreak was much worse than the current one. Yet, grocery-store egg prices increased only slightly (after correction for inflation) during that outbreak and then dropped to a 15-year low after the flu crisis was over. Why? The prices of main inputs (feed and fuel) were in a seven-year trough. Reviewing USDA records of corn prices and production costs 2013-2019 made me very glad I was not growing corn. Average net farm income from corn in that entire time was negative! Soybeans were a better bet during that time, but not much better. During this time, the grocery stores mostly passed the lower production costs onto customers. The 2015 price peak was driven only by temporary shortages while the hen houses were repopulated after the avian flu. You were paying for that low grocery-store egg price with some of your income tax dollars spent on culled chickens and commodity supports. At least, those of you lucky enough to be paying income taxes were.

So, in 2016-2019, the inflation-corrected price for eggs dropped. In 2019, the price was nearly at an all-time low. In 2021-2022, feed grain prices increased by 83 percent, and the pandemic drove other costs including labor up. So, some increase in egg prices had to show up in 2022. That would explain the inflation-corrected price finally getting back to the 1980 level, before the dramatic improvements in laying-hen and grain genetics.

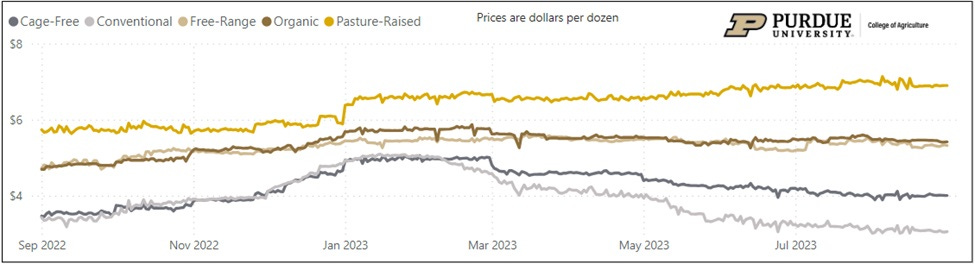

In 2023, the prices that corn and soybean farmers got for their crops tanked. Surpluses drove one of the largest single-year decreases in farm income ever. Looks like those surpluses and low grain prices will continue for the next few years. How is that reflected in egg prices at your grocery store? The price of some eggs dropped in 2023, according to Purdue’s egg price dashboard. But the prices of pasture-raised, free range, and organic eggs stayed high. In fact, pasture-raised egg prices went up!

What happened to keep the price of those eggs so high? Are egg lovers inelastic about their concerns for factors other than protein and baking ingredients? Consider this: Vital Farms “went public” (stock symbol VITL) a few years ago. A lot of people are making money on these eggs who are not farmers and egg-handlers and grocers. I paid $4.60 more for the VF eggs than I did for the FL eggs. How much of the $6.99 (or $7.32 in some area stores) per dozen VF eggs goes to stockholders instead of farmers?

In my searches for contract leaks from third parties, I came across an interesting comment in a business analysis (by Cristain Velasquez): “Farmers choose to work with Vital Farms despite sacrificing income. Traditional methods of egg mass-production are more profitable but don’t align with the shared values of Vital Farms and their farmers.” In addition to paying their farmer-partners less to begin with, VF has not reduced the retail price as the feed costs dropped over the past eighteen months. In 2023, the company’s net revenue was 35%, their highest ever. This was a 2000%-plus increase over 2022. At 35% net revenue, $2.45/dozen and possibly more is going to shareholders. VF is Certified B Corporation, a “beneficial” for-profit corporation which voluntarily meets some “transparency, accountability, sustainability, and performance” goals set up by a private-sector group (B Lab). That certification costs money that doesn’t go to farmers, either. I’d rather give that directly money to a farmer neighbor.

While contract grower arrangements and limited market options make farmers’ lives challenging, it’s not a lot of fun to be the hen, either. The VF hens have more room to roam, but the VF business model hasn’t translated into improving what happens before those hens get to that pasture. This includes the destruction of day-old male chicks and beak clipping of the laying hens. I was surprised to learn that beak-clipping is done in a pastured flock where I would have expected their beaks to be worn by pecking food out of the dirt. It’s not something we had to do on our farm. It’s also not something that my neighbors’ little flocks need, probably because they are wearing their beaks down in the sandy soil here. The dirty little secret of laying hens is that the best layers are the most aggressive and most likely to insist on being at the top of the “pecking order” and will resort to violence to get there. Once blood is drawn, there is often a “pecking party” that ends very badly for whomever is on the bottom. Yes, hens gave us that “pecking order” expression. Layer genetics is a balance between egg production volume and hen aggressiveness, especially where hens are housed together. Beak clipping reduces the damage hens can do to each other in a pecking party. It also reduces their pasture-foraging ability.

Even without pecking parties and avian flu, a laying hen’s life is fairly short. She’s fertilizer or in Fido’s dinner bowl in couple of years. Pushing the genetics to increase egg production per unit of feed and laying rate has resulted in high rates of ovarian cancer in laying hens. The only good news here is that women have benefited because ovarian cancer researchers have learned a lot from hens.

Vital Farms has a subsidiary working on technology to determine the sex of the chick before hatching. This would eliminate post-hatching killing of male chicks, but that technology development seems to have stalled short of deployment. It’s been about eight years of relative silence since the initial chatter about this technology. Most of the European Union has banned destroying male chicks over the past few years, requiring hatcheries to route the male chicks into broiler production instead of euthanizing them. Destroying male chicks is still normal industry practice here in the US because the genetics for egg-producing chickens result in lower body mass and feed conversion which in turn makes raising the male chicks for the dinner table a losing proposition. In the meantime, VF’s advertising and corporate structure have made them a juicy target of People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA). PETA has sued VF for “misleading advertising” of humane egg production while engaging in practices such as mass euthanizing of male chicks and beak clipping. I’m not a fan of PETA. It’s not that I mind their advocacy of veganism, but they have a “ends-justify-means” mentality. They would like to end all “humane certifications” because they believe those certifications lull consumers into eating more animals and animal products by reducing consumer guilt. PETA also claims that these certifications trick consumers into paying a lot more for only marginal improvements in the animals’ lives. They may have a point there — is “Humane-Washing” a word now?

Despite PETA’s lawsuits, Vital Farms seems to have a strong consumer fan base. In fact, a secondary market has sprung up around VF. You can buy “vintage” Vital Farms lapel pins on eBay – basically, they say “Founded in 2007” with the logo. You can buy VF eggshells sterilized and crushed to use as plant fertilizer on Etsy. At $10/pound, it’s a pretty expensive source of lime. I confess to sterilizing my eggshells (a tray of them in the oven when it’s already heated to bake cookies does this for free). I grind them to powder in the Vita-Mix. I use some to prevent blossom-end rot when planting veggies, some for a calcium supplement for friends’ hens, and some for a calcium supplement for me. But hey, I am a little OCD about not wasting any gift from a critter.

The sad truth is that it is no more fun to be a laying hen than it is to be a dairy cow in a world where food is so cheap. Or perhaps I should say, in a world where the farmer is getting paid so little for her produce. The price you pay for eggs and milk in a grocery store may have little correlation with what the farmer is getting!

Kroger-Albertson Anti-Trust Findings:

Kroger Raised Milk and Egg Prices Beyond Inflation Costs, Exec Testifies: Report - Business Insider

Kroger Admits to Price Gouging: Evidence and Impact | Explee

Inflation and price of eggs:

https://www.usinflationcalculator.com/inflation/egg-prices-adjusted-for-inflation/

Eggs price inflation, 1935→2024 (in2013dollars.com)

Egg production and consumption:

Facts & Stats - United Egg Producers

Costs contributing to egg production:

The Layer Ledger: Economics of Egg Production and Pricing - HusFarm

Commodity Prices:

USDA ERS - Commodity Costs and Returns

Purdue University

Center for Food Demand Analysis and Sustainability (CFDAS) and Egg Price Dashboard:

Egg Prices - Center for Food Demand Analysis and Sustainability (CFDAS) (purdue.edu)

Certified Humane Standards for Egg Layers:

Feeding Poultry:

Feeding Soybeans to Poultry (agriculture.com)

Whole soybeans in diets for poultry | The Poultry Site

Vital Farms Website:

Forbes on Vital Farms:

https://www.wattagnet.com/egg/article/15665893/us-vital-sees-2000-increase-in-net-income-for-fiscal-2023

B Lab Corporation Certification for Social Impact:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/B_Corporation_(certification)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/B_Lab

PETA Suits:

PETA-affiliated lawsuit accuses Vital Farms of lying about ethical treatment | Food Dive

PETA continues to mislabel Vital Farms on welfare claims | WATTPoultry.com (wattagnet.com)

European Ban on male chick culling:

Male chick culling to stop in France by year end | WATTPoultry.com (wattagnet.com)

Vital Farms Pasture Raised Hens Grade A Organic Egg Shells Hand Crushed 5 Lb - Etsy

Vital Farms Business Relationships with Hatcheries and Farmers: Vital Farms (extended): An Analysis by Cristian Velasquez | by Cristian Velasquez | Medium

Thanks for another in-depth article about an important agricultural topic, Kristin! I always learn something from your articles and appreciate that your writing style starts from your long-time experience on a farm, which you supplement with additional research to update your knowledge per current scientific understanding, regulatory policies, and market forces.