Eighteen Thousand Dairy Cows, RIP

And the decades-long journey to this tragedy.

EIGHTEEN THOUSAND cows died in an explosion this past week on the South Fork Dairy Farm in Texas. A farmer was also critically injured in the same explosion. The facility – over 2 million square feet under a single roof – was a total loss. The cause is still under investigation, but overheated ventilation equipment removing methane from the facility is a prime suspect. Cows digesting grass (fresh or hay) produce a lot of methane.

Those 18,000 cows were not “just cows” to the people who worked with them, but individuals. Their loss was both an emotional and financial disaster for that farm. This sudden tragedy has roots in a larger tragedy, a slow-motion disaster for US dairy farmers lasting over fifty years. This larger tragedy is hidden in that number: EIGHTEEN THOUSAND. Given the 9.45 million dairy cows in the US (that’s USDA’s 2022 number), nearly 0.2% of all US dairy cows died in one explosion. It was nearly 3% of all the dairy cows in Texas, fifth largest dairy production state. How did we get to a place where this was possible?

Dairy farmers work harder than anyone. Cows must be milked at least twice a day, 365 days a year. This was brutally hard work for the dairy farmers of my formative years, where a large dairy might have a hundred cows producing milk at any given time. And remember that you’ve got to fit care of land and cattle and crops in around that milking. But hard work did not save those dairy farmers of yesteryear.

I saw the beginning of the end of those dairies. I was much too young to recognize what was happening, however. In 1965, Excalibur Farms – my family farm -- had its start with a failing dairy. And that dairy had its start with another farm operation going under after a family tragedy. Judging from the tombstones in the cemetery on the farm, the owner who lost his life to an “accidental” gun discharge in 1956 or 1957 was at least the fourth generation of the Price family farming that land. The formerly prosperous farm was auctioned to pay the bills for improvements – which it didn’t. I’ve heard that the fellow who built the dam for the pond was never paid. A cousin of the deceased owner bought the farm at the estate auction on a low bid, but he could not hold onto it either. Will and Lois Hardstock bought the farm from him in 1957. That year, the average price of a gallon of milk in a US grocery store was $1 per gallon. That’s $8.70 in 2023 dollars – the highest milk had been in the 20th century. Dairy farming probably looked like a good bet to this young family.

Will and Lois named the farm “Willow Hollow Farm.” The name was bit of a pun: “Wil-low” was a mashup of their first names, and there were great old willow trees in a hollow formed by a creek beside the farmhouse. Those willow trees had trunks over three feet in diameter and low-hanging branches, perfect for climbing by children. Will and Lois had a houseful of children. I remember seven, but my brother claims that three of them were actually cousins. And they were very hard workers – especially Lois. One of the children had a fascination with matches, unfortunately. He burned the main barn down and almost burned the house down. One room in the house was gutted by fire when we moved in. The smoke-stained wallpaper in the rest of the house was hastily covered by paint.

After the barn burned, the Hardstocks took out a second mortgage to build a new barn, a modern 3-stall dairy, and a feedlot. The “Milkhouse” they had built was a marvel in its day. It had a “tandem, side-opening” style milking parlor. The long, narrow building had one room with two levels. The cows would come off the pasture and line up on a ramp entering the west end of the building on the upper level. A person down on the lower level could pull a cable to open a sliding door to admit them one at a time. Other cables operated gates to the milking stalls. One cable pull opened an empty stall to the next cow coming in on the west ramp, and another cable pull would dump a ration of grain from an overhead auger into a trough in front of the cow. Once that gate was closed again and the cow was enjoying her snack, the milker on the lower level could scrub the cow’s udder clean and connect the milking cups to her teats without bending over. Vacuum pumps did the rest while the milker moved to the next cow and get her scrubbed and cupped, then the next.

When the first cow had given her contribution, the milker would remove the cups from her teats and pull another cable to open the forward gate so she could exit toward the east end. There, another cable-operated door and ramp would take her to the silage bunker for the remainder of her meal (corn or hay silage). Her stall’s rear gate would be swung open to admit the next waiting cow. The second stall’s occupant would be finishing then – and so on. Two people could milk fifty or sixty cows twice a day there if they hustled.

The milk was pumped into a large stainless-steel tank in the next room through transparent plastic pipes so the milkers could monitor the flow. The co-op truck would come and empty that tank every day, to get the milk into refrigerated storage and processing. The dairy had to be scrubbed from top to bottom, its pipes and tank flushed, every day. This era had brought a new understanding of diseases like Brucella. Your milk was graded by the cleanliness of the dairy as well as butterfat content.

And here is where Willow Hollow Farm’s story begins to end. The price of milk had been on a slow but steady march downward since 1957. In 1965, the average price of a gallon of milk in a US grocery store was $1.05 per gallon, but inflation was taking a toll. That $1.05 was $8.14 in 2022 dollars. Will had hired a man to help him, and one of that farmhand’s jobs was cleaning the dairy after milking. Lois Hardstock – who kept the books as well as a zillion other farm, household, and parenting chores -- would follow up to check on the dairy’s condition after the farmhand left for the day and the children were in bed. She frequently found that the milking parlor was not clean enough, and she would clean it again herself. This apparently went on for years. One day she told Will that she was going to clean the house instead of the dairy, as she was exhausted as well as ashamed of the condition of the house. Will was slow to understand the implications of her decision. A few weeks later, the dairy inspector cancelled Willow Hollow’s class A dairy license. Class B milk prices were much, much lower. Too low to pay the bills for feed and labor. Or the grocery bills.

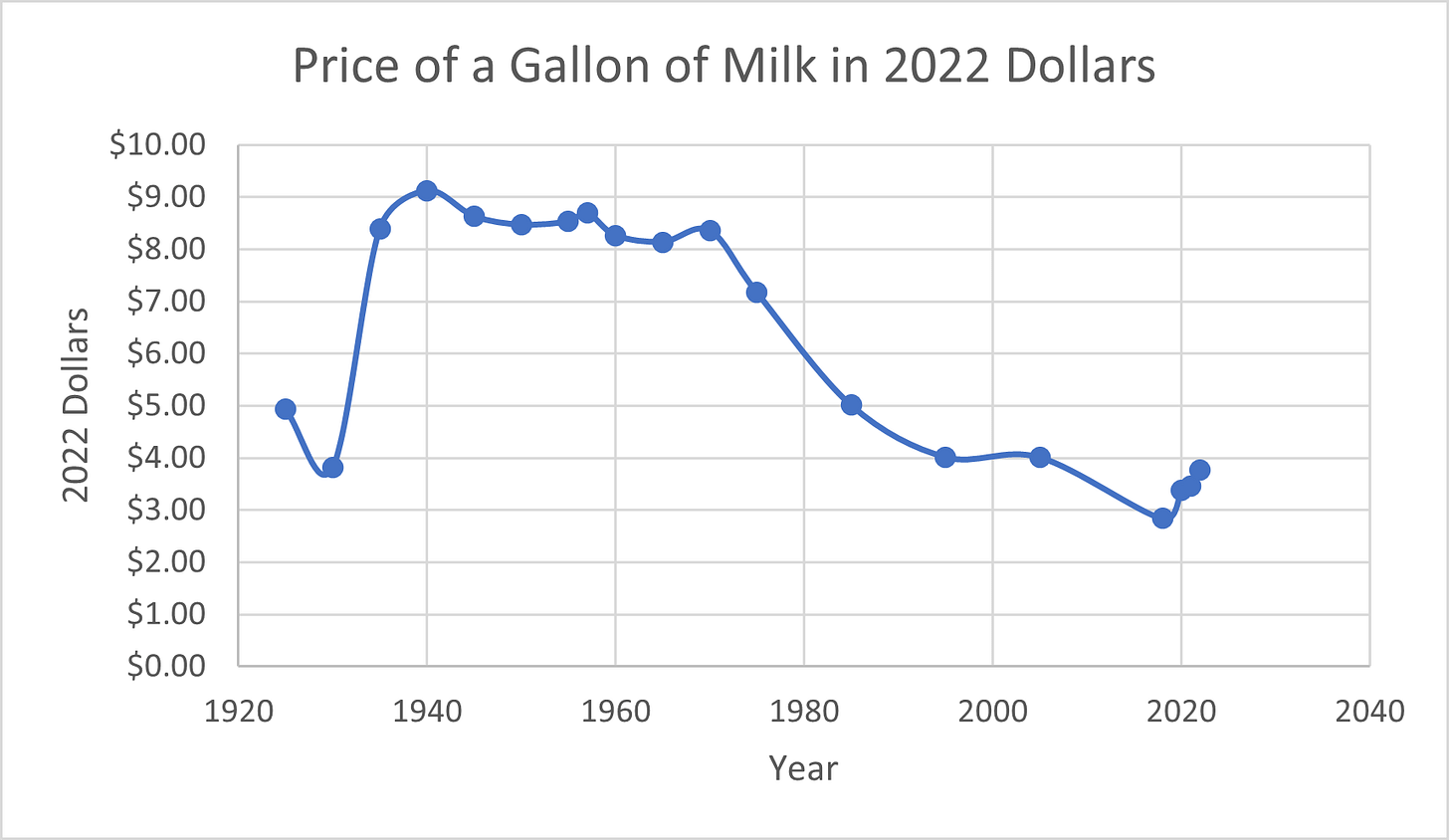

Price of a gallon of milk in 2022 dollars. Willow Hollow was doomed even without the loss of their Class A license. USDA data (USDA ERS - Dairy Data)

At that time, my parents were a year into looking for the farm where they were going to “raise farm kids.” That spring, my parents stopped by the only bank in Madison County, Virginia to discuss possible financing on another farm on their short list. The banker told them that he was going to have to foreclose on Willow Hollow Farm, and he hated that. Perhaps they would go look at this farm before they made an offer on any other? The price would be good and it was a very pretty place with “more potential than the first look would suggest.” Best of all, if my parents made an acceptable offer, he would not have to put a foreclosure on the record of a hard-working family -- and it would not be on the front page of a small-town newspaper.

That first look was disappointing, due to how overwhelmed this family was. I recall some trash blowing across the yard in front of the house. But my mother could see the natural beauty of the land and announced that she had finished looking for “our” farm. My next memory is of hanging on the fence by the cattle-loading chute, watching as Holstein after Holstein was brought out and examined by a couple of men. They clapped a numbered sticker onto the hips of most of the cows and loaded those on a large truck. “Daddy, where are they taking the pretty cows? Will they come back?” I asked. My father told me we were getting cows of a different color. At five-going-on-six, I had no idea what milking a cow entailed. My parents decided that they were not cut out to be dairy farmers. Dad was still active-duty military assigned to the Pentagon, a hundred miles away. Mom would handle the farm by herself with three young kids during the week until he retired, with Dad coming down for weekends. And we are definitely not morning people. The “cows of a different color” were Black Angus, which we raised for beef.

It strikes me now that the Hardstock kids were completely absent from that memory of the cows being sold. Those kids were losing their home of eight years, perhaps the only home the younger kids remembered. Now, nearly 60 years late, I wonder how the Hardstock family felt about selling those cows. Were the kids crying in the house? Had they named those gigantic black and white cows? They had probably raised many of them on bottles, as every farm kid’s early chores include bottle-baby duties. Dairies have more bottle babies than any other kind of farm, because the calves are taken from their mothers as soon as they have ingested enough colostrum to trigger their immune systems. Those bottle-fed heifers became cows that probably followed the kids around the pasture. Their bovine friends were being hauled away by strangers.

Or worse. A few years later, during my dinosaur craze phase, I found dozens of large bones up in the woods. The femur of a Holstein looks a lot like a dinosaur bone to a small kid dreaming of a great paleontology find. My family teased me for years about my collection of large cow bones hidden under my bed. It was years before it occurred to me how and when those old bones got up into the woods. What happened to the Holsteins that did not get stickers from buyers?

Another early childhood memory surfaces now as I think about this: standing in the tank room of the Milkhouse, adults talking over my head while I marveled at the complex network of transparent pipes and the huge stainless steel tank. That meeting was probably the sale of that tank, because I never saw it again. Perhaps that was part of an auction, like many we would attend in those years, looking for equipment bargains as other farm operations changed hands. I don’t hear an auctioneer’s chant in that memory, so perhaps it was just my parents systematically selling off everything they did not need. My parents sunk all their savings into starting Excalibur Farms and much of their subsequent cashflow went to paying off a second mortgage to the Hardstocks. Those first years were difficult in a way that I only understood recently when I was researching deeds for the property. I found the record of that second mortgage. Their monthly payments during the first five years were equal to my father’s entire military retirement pension. No wonder there were arguments about money. And questions like “what were we thinking?”

With the exception of a single stall that we used to milk one cow for a few years, that marvelous milkhouse became a shop and then storage for over fifty years. The concrete work on the feedlot and ramps was shoddy and quickly cracked; I had much of it removed over the past twenty years. The Milkhouse became a forlorn cinder-block hulk stuffed with things that are too good to throw away but not good enough to use.

Photo: What remained of Willow Hollow Farm’s milkhouse in 2020, over 60 years after its construction. You can see the cows' entrance on the left, and their exit on toward the middle. The ramps to those doors are long gone. An auger took feed from a grain bin into the milking stalls through that hole in the eaves.

We did have a milk cow for a few years. Just one. A dairy farmer whom my mother helped rehabilitate from an injury gave us a Guernsey. He said that the cow “just needed more attention” than he could give her in his large dairy. At least, his dairy was large for the late sixties. He may have been milking a hundred cows. I immediately named this tan and white cow Milky Way, but the first few days during which we learned to milk her, she gave very little and that little was far more cream than milk. That must have been one very stressed cow, considering our fumbling that first week. Dad very quickly acquired a small portable machine to milk her, much to her relief, and moved the operation into a stall of the milking parlor. She did not seem to mind that our morning milking was never at 4am. The butterfat content in her offering went way down after we learned how to make her comfortable, but it was still higher than average. I have fond memories of butter made in the Waring Blender, and ice cream. Really rich ice cream: the recipe called for a dozen egg yolks in addition to heavy cream. Good thing we had some chickens to help that cow. But Milky Way also gave far more milk than we could consume and give away. Before you ask, no, we did not drink raw milk. Mom found a small pasteurizer and we used it religiously. She probably figured that was prudent considering not just her knowledge of Brucella, but her knowledge of the particular kids doing the milking! We did not have a dairy inspector because we were not selling milk.

I had a taste of large dairy operations in the early 1970s, with 4-H friends. Because my dairy friends could seldom be spared from milking chores, I overnighted at their farms much more often than they could visit me. I especially appreciated times with the Wolfinger family. Mrs. Wolfinger was a single mom of four, a transplant from the northeast . She had a degree in animal husbandry – very rare for a woman in those days. Perhaps our families were drawn together due to strong women or perhaps it was our shared history of being “come lately” transplants under a great deal of suspicion from long-time Madison residents. Mrs. Wolfinger managed Laneway Dairy’s herd for Mrs. Hayward. The story was that Mrs. Hayward had decided that she was going to breed the best Ayrshire cows ever, damn the snide remarks about cow manure from her old-money clique with their fancy horses and foxhounds. She was often in the barn discussing cows with Mrs. Wolfinger and various experts from Virginia Tech, looking just like any other hard-working farmer. Dad planted and harvested Laneway’s corn for several years. Dad preferred things with roots to things with hooves, but the women in our family (Mom and me) completely understood the Laneway women’s obsession with cows.

Sleepovers at the Wolfingers would include a 4am hike across the biggest road in the county and several pastures, because they did not own a car. We crossed fences in the dark on rickety stiles slick with frost to get to the dairy barn. Laneway’s open-stanchion milking parlor was huge compared with our Milkhouse. I never counted noses, but I’m sure that dozens of cows were in there at once. The cows lined up in rows with noses in a trough to eat breakfast while the milkers moved carts of equipment behind them to milk them. I secretly thought it was “not very modern.” I remember wishing we could move our unused Milkhouse to their farm. But a determined woman and four kids who knew exactly what to do could feed and milk over a hundred cows in that open-stanchion barn in under three hours. Now that I read efficiency studies, I know that open stanchion arrangement was actually much faster than milking that many cows would have been in our Milkhouse. Unfortunately, it was far more labor-intensive. I suspect that the extra help from a sleep-over friend who yawned her way through whatever she was told to do – usually dish out feed -- did not cut the total time. I would move carefully around those cows because I did not want to startle them while someone was behind them scrubbing an udder. As my mother often said with a grimace, being stepped on by a cow is a not-so-free ticket to the Emergency Room. She had the foot to illustrate that point. Dairy cows are usually bigger than beef cows but a lot more domesticated. The beautiful red and white Ayrshires quickly warmed up to me when I scooped grain for them. Wet noses and whiskers tickle your face and the occasional affectionate brush with a long rough tongue is a special treat. The smell of a winter barn warmed by a hundred cows, their cow-fragrance mixed with smells of grain and hay and raw milk and – yes, even the manure -- is wonderful. I wanted to buy one of their Ayrshire heifers for a 4-H project.

I would be wide awake by the time we left Mrs. Wolfinger hosing down the dairy. We had to dash the half-mile back to the house to get ready for school. Modesty was a casualty as all five of us cleaned up and dressed for school in a small house with very limited plumbing. We’d make sandwiches for both breakfast and lunch and be back out on that road when the school bus showed up at 8am. We’d eat peanut butter sandwiches and drain thermoses of milk for breakfast on the bus to school. I loved those sandwiches – Mrs. Wolfinger had taught her kids to bake bread and make jam. They made their own clothes, too. They inspired me to learn these things.

Afternoons with the Wolfingers had about an hour and a half between school-bus stop and evening milking. In that brief interlude, I helped one of the girls train a horse she had bought with her milking pay, then it was milking until 8pm. Mrs. Hayward considered the Wolfinger kids parttime farm employees, something no longer legal. Now, anyone outside of the farmowner’s family has to be at least sixteen to work with large livestock. Each of the Wolfingers had a tidy savings account for college. Those visits helped me understand why dairy farmers’ lives outside the milking parlor were chaotic and homework was done on the school bus. I came to understand my parents’ decision to raise beef cows as well as their veto of my proposed 4-H Ayrshire heifer project. Other people’s dairy cows – like other people’s kids -- are fun in small doses, but then you can give them back and sleep until daylight the next day.

Laneway Dairy had an advantage over most other dairies: Mrs. Hayward did not have to keep it in the black with milk sales alone. Her main interest was improving dairy cattle genetics. People were paying more for those high-production genetics than for milk. But Laneway is long gone. Black Angus beef cattle graze in fields once populated with Mrs. Hayward’s famous red and white Ayrshires. The little cottage the Wolfingers grew up in is now rented to someone who can afford a late-model car. As I passed it recently, I saw someone waiting for a break in traffic to pull out, and I remembered that the house didn’t even have a driveway when I was a school-age visitor. I suspect the plumbing has been improved considerably, too. The road slicing Laneway into two pieces, tenant house on one side and dairy complex on the other, is now a heavily-traveled divided four-lane artery that would be much too dangerous to cross on foot in the dark. The neighboring dairy is gone, too. The dairy a few miles north of Laneway -- run by the fellow once voted “Young Farmer of the Year” and who was on the county Board of Supervisors -- is gone now, too, collapsing in a spectacular bankruptcy case. There are over three times as many beef cattle as dairy cattle in the US now.

I read somewhere that nine out of ten Virginia dairy farms have gone out of business, but I don’t know exactly when they started counting that statistic. Most dairy statistics in the US only go back to the 1990s, with only a few back to the 1970s. The national statistics show a 9-out-of-10 loss starting in the 1990s. The 2019 count for dairies in Virginia was only 505, which suggests our state may have lost at least 4,500 dairies along whatever road that is. The current numbers vary from source to source, depending on how they define “dairy.” Some statistics include farms that are not licensed to sell dairy; these sources claim over 64,000 dairy farms in the US. Sources that count only the farms licensed to sell dairy products come up with a 2021 number under 30,000. I don’t think Willow Hollow Farm was ever counted, having been lost in 1965, which suggests the reality is worse than the dismal statistics.

Individual farmers respond to falling commodity prices by figuring out how to increase production per unit cost. Price supports don’t do what you think they will do. US farm price supports are more about protecting the US consumer than the US farmer, unfortunately. I’ll unpack that more in future newsletters. For now, just keep in mind that a price support effectively becomes THE price at the farm as individual farmers try to survive while consumers demand enough money after-grocery money to buy TVs and cars. This essentially fixed commodity price has led us to the point where US dairy farmers have become so efficient that just one state – Wisconsin – produces more milk than all of Canada consumes. This is a problem for Canadian dairy farmers.

About 15% of US dairy production is exported. Canada is our leading export market US butter and processed dairy products. Mexico is our leading export market for US cheese and nonfat dry milk. During the 2020 presidential campaign, I saw a lot in the news about the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) on Trade replacing NAFTA and “saving dairy farms.” The new dairy-related USMCA provision became effective on July 1st, 2020. It was supposed to give the US dairy farmers "increased market access for selected dairy products." The USMCA has only one dairy-related item in it that NAFTA did not have: it eliminated "Class 7 Dairy Price Supports" in Canada. Class 7 is "ultrafiltered" milk ingredients such as skim milk powder and milk proteins. The Canadians call this "diafiltered." The US does not have a Class 7, despite having invented it. Canada did not have this class either when the original NAFTA was signed. This product class is a fallout of the recent resurgence of butter consumption. The US was the sole manufacturer of it when USMCA was signed, and Canada agreed to end pricing that effectively limited the export of this particular US dairy product into Canada. US-Mexico trade policy for dairy did not change at all between NAFTA and USMCA.

Several months into the USMCA, however, the farm country headlines declared that the new Class 7 provision is unenforceable. Furthermore, the US and Canada have been fighting continuously over provisions carried forward from NAFTA, which allow Canada to charge tariffs on dairy imports from the US above a certain level. The US won one dispute in 2022 over how Canada allocated the tariff-free US import quota to its dairy processors, but another dispute is already well underway.

These dispute details are complicated enough to fill a book, and one or two marginal export markets are not going to save many US farms. So I will jump back to the big picture: The US overall has lost over HALF of all the dairy farms we had in 2003. Since the beginning of the Great Recession in 2008 and through 2016, we lost (on average) 3.5% of all licensed dairy farms per year. In 2017-2019, that loss has increased to an average of 6.66% per year. The worst year percentage-wise was 2019 at 9%. Despite the pandemic, 2020 looked a little better at “only 7%” decline in the number of licensed dairy farms.

Be careful with reading percentages, however: in 2003, the loss of 3,550 licensed dairy farms was a 5% loss while in 2019, the loss of 3,281 farms was a 9% loss because there are now only half as many total farms. The price of milk started to recover at the end of 2019 -- to its 2014 level -- but that was too late for over 3000 dairy farms. Virginia lost 60 licensed dairy operations in 2018. Wisconsin led national losses with 780 farms in 2018. Wisconsin also led the loss-list in 2020 with 610.

Yet the milk supply is still high enough to depress prices. What's happening? The number of dairy cows in the US actually increased a little (almost 2%) in the last 20 years. Milk production per cow has increased almost 12% in just the past ten years. US farmers have done what they always have when squeezed between input cost increases and gross income reductions: increased productivity. Unfortunately, this is only a short-term individual solution for a systemic long-term decline.

The bottom line: We are losing many dairy operations but the remaining operations are getting bigger. In 1970, the average US dairy milked 47 cows, with Willow Hollow Farm close to the average. In 2003, US dairy farms averaged 133 cows per farm. In 2020, they averaged 273 cows per farm. Hidden in that average is the fact that over a third of US dairy production now comes from farms milking more than 2000 cows (up from about 3% in year 2000). Last week’s news suggests that some dairy farms are milking far more than 2000 cows a day! Dairy production is also shifting westward. If you count all the cows being milked on all the remaining dairy farms in Virginia alone, you come to a total that’s only 40% of the number of cows milked in 1970 in the state. The surviving Virginia dairies have gotten much bigger, but the dairy industry is consolidating more in particular regions – like California in first place and the dairy stronghold like Wisconsin in second place. Texas is fifth in dairy production. Come to think, the only thriving dairy I know near our family farm in Virginia milks sheep and making exotic gourmet cheese, a high-markup product. No cows there.

Shadows of the demise of Willow Hollow fall still and long over today’s dairy industry. The cost of the equipment is a big factor, pushing more consolidation. It’s not just the milking parlor and its equipment. Systems for handling the waste from the herd in compliance with environment regulations cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, even millions, for each farm. Methane capture regulations will add a lot to this capital requirement. This much up-front investment means large debt loads.

Labor cost and availability are also large factors. It’s brutally hard work and families don’t have enough kids to milk thousands of cows before and after school. Dairy cows are now most likely to be milked by hired labor. Labor laws now prohibit hiring the neighbor youth under 16 to work with large livestock, so that country youth rite-of-passage has been replaced with an older, full-time workforce. Many dairy farmers I know now speak “Spanglish.” Their equipment operating instructions and cleaning directions are in both English and Spanish.

In 2005, we bought a used feed grinder from such a dairy, near Roanoke, as they upgraded to a much larger-capacity system. Like many surviving dairies, that dairy was milking 24 hours a day, seven days a week, in a highly-automated rotary milking parlor. The equipment even attached the teat cups to the cows’ udders while they munched their feed on a huge, rotating turntable. Per-cow milk production now is so large that many dairies milk their cows three times a day instead of just two. That means a constant stream of cows entering the milking parlor around the clock. Three labor shifts a day, every day. Can large operations like that afford those highly automated milking parlors, manure-handling systems, and payrolls without being only a few weeks’ production loss away from financial disaster like Willow Hollow Farm was? That Virginia dairy really impressed me as huge but the west Texas dairy that just lost its entire herd was many, many times its size.

On the consumer side, the dairy industry faces competition from all sorts of beverages including plant-based “milks.” Per capita cow’s milk consumption in the US has decreased 46% from 1975 to 2021 (almost halved). During this same period, the production of the average US dairy cow more than doubled. We do eat more cheese, butter, and yogurt than we did in 1975. Some of us, anyway. I developed a dairy allergy, so my own dairy consumption is zero. Even though I no longer have any personal interest in dairy, I keep an eye on this farm sector. It is highly regulated and tracked, requiring licenses and testing of individual cows and facilities. Thus we have more data about what's going on with dairy farming than we do with any other farming sector. Problems there are going to be problems somewhere else before long, if not already. Take labor. Wolfcreek Farm, which specializes in organic grass-fed beef, cannot expand their herd to the carrying capacity of their pasture because they can’t find enough workers to tend the additional cows. My own exploration of a transition to horticulture was stillborn over the availability of labor and cost of equipment as well as zoning. You can buy equipment to reduce the number of employees, but only to a point.

Milk production per cow over the past fifty years. USDA Data (USDA ERS - Dairy Data; Milk: Production per Cow by Year, US (usda.gov))

The Hardstock family ended up on the Virginia coast, where they ran a small marina – as far from dairy farming as Will and Lois could get. Their transplanted work ethic made that operation successful. Most ex-dairy farmers do well, even as they joke about their relative “post-dairy sloth.” The old Milkhouse was the last trace of the dairy phase of our farm’s history and the Hardstock family’s difficult tenure. The main barn they built remains, but we transformed it into a lambing barn decades ago. Even the giant weeping willow trees in the hollow are gone. Many died after Hurricane Camille’s rains caused the creek that fed them to change course in 1969. All but one of the few willows surviving Camille’s ravages were destroyed in the 1995 flood, which turned the entire hollow into a raging river. There’s only one scraggly willow clinging to life now. It’s a twisted sentinel to spring, streaming bright yellow-green tears on its wispy branches just after the crocuses bloom and just before the daffodils open.

Photo: The only Willow tree that survived the 1995 flood , last daughter of those giants that gave Willow Hollow its name.

The only other remnant of Willow Hollow Farm I have are three metal canisters that the Hardstock girls gave me as a parting gift in 1965. Two have a blue oriental motif and one has a foxhunting motif. I have kept them all these years on one mantle or bookshelf or another. A faded label on one says that they originally contained toffee. Perhaps that candy was a Christmas or birthday treat, making their presentation to me a special gesture for those girls. I remember seeing their very sparsely-furnished bedroom in the farmhouse, the room that became my bedroom, that day. Those girls did not have many treats. The tins are somewhat the worse for years of holding childhood projects stored with grubby little hands. I have kept those cannisters for 58 years, not because they have any monetary value, but because their presentation to me seemed very important to those two girls. They remind me of the changing of the guard over the land. I wonder how those girls and their brothers have fared since 1965. I wonder how often they think of the farm that shaped them. I wish we had not lost touch.

I look at those cannisters now as I think of eighteen thousand dead cows, lost in a single dairy accident. South Fork Dairy was milking as many cows in one day in 2023 as the Hardstock family milked in an entire year in the early 1960s. And the entire dairy was wiped out in a single explosion.

Photo: The toffee tins that the Hardstock girls gave me as they left the farm to us in 1965.

Thousands of cattle killed in explosion and fire at Texas dairy farm | CNN

Milk: Production per Cow by Year, US (usda.gov)

Number of Dairy Farms in the U.S. | The number of cows per herd is on the rise. (usfarmdata.com) (now 802 dairy farms in Virginia)

USDA ERS - Dairy Data (Lots of spreadsheets here for you data geeks)

Number of beef and milk cows in the U.S. 2022 | Statista

USDA ERS - Sources, Trends, and Drivers of U.S. Dairy Productivity and Efficiency

Portable Milking Machine Components And Operation (dairypundit.com) (If you are curious about the equipment)

Thanks for sharing some of your childhood memories along with your thought-provoking analysis of the ever-morphing dairy industry in the USA. Love the photos from your old family farm!

Kristin, this is priceless. Keep up the good work. You're telling the story of the heart of farming America. And it's often remembered (at least by me) but seldom told. Thanks, Jim P