How's the weather tomorrow?

And next week and next season....

In late January, I took a trip back into one of my past lives, for NASA’s Day of Remembrance. This ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery honored the 17 fine people who lost their lives on NASA’s worst three days: the Apollo 1 test fire (January 27th, 1967), Space Shuttle Challenger (January 28th, 1986), and Space Shuttle Columbia (February 1st, 2003). You will be reading this just after the 59th anniversary of the Apollo fire, the 40th anniversary of Challenger’s explosion, and the 23rd anniversary of Columbia’s re-entry breakup.

The closeness of these anniversaries has often made me wonder if I (and perhaps the entire National Aeronautics and Space Administration) should just spend this week underneath the nearest bed. I was still in the US Air Force when Challenger exploded, but I joined the space program a few months later, where my work included helping return the Space Shuttles to flight. I was a Flight Controller in Mission Control for the 1990 deployment of the Hubble Space Telescope (STS-31). Later, I helped develop a free-flying robotic camera to inspect the Space Shuttle exterior, because we had frequent launch debris damage to the heat-shielding tiles. Unfortunately, I was not able to see it through to routine use on every flight. I was working on Space Shuttle safety upgrades when Columbia disintegrated on reentry in 2003. Tiles damaged during launch failed to protect the Shuttle from catastrophic re-entry heating.

At the Arlington ceremony this year, our new NASA administrator Jared Isaacson and Dr. June Scobee Rodgers laid wreaths and flowers at the Tomb of the Unknowns, the memorials to the three crews lost, and the graves of those astronauts buried there. Administrator Isaacson was not quite three when Challenger exploded and not quite twenty when Columbia disintegrated. He’s made billions in payment processing and used that fortune to sponsor his own space missions. Dr. June Scobee Rodgers is the widow of Challenger Commander Francis “Dick” Scobee who turned that tragedy into four decades of motivating young people to study science and engineering through the Challenger Centers, which she founded with other Challenger families.

As our new Administrator read condolences to our group, I looked around and saw several prior NASA Administrators including Sean O’Keefe, who headed NASA when Columbia crashed. I suspect I wasn’t the only one praying that the new guard would not repeat the mistakes of the old. You spend the rest of your life asking if you could have done something different to prevent the loss of your colleagues.

For decades as an engineer, I marked these anniversaries with a letter to my engineering teams, perhaps reflections on safety or the responsibilities of engineers or how smart technical people can be blind to a disaster in the making. Because good people can make bad mistakes, and you can die doing this stuff. But this trip also gave me a glimpse of the Earth Information Center display at NASA Headquarters. Our space program has given us amazing earth-monitoring capabilities, and I decided to commemorate these anniversaries with this letter to my farm and food colleagues instead. Earth observation advances have transformed agriculture. Fifteen satellites—many joint projects between NASA, Department of Defense (DoD), and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)—and our Space Station are currently monitoring current weather, storms, lightning, precipitation, atmospheric rivers, dust, air quality, fire, soil moisture, ice thickness, land elevation, biomass, radiation, energy reaching crops, vegetation cover, and crop health.

Come to think, our space program has saved thousands of lives and improved the quality of millions of lives. I hope that’s some consolation to those who lost friends and family when we let down our guard on the path to making this vision a reality.

Tragedies can shape organizations’ culture for generations, like the Apollo 1 fire defined NASA’s Mission Control. Leadership—Gene Kranz headed Mission Operations then—pounded the lessons of that tragedy into my generation of Flight Controllers along with those of Challenger. Mission Operations’ “Res Gesta Par Excellentiam” (Achieve Through Excellence) motto was born in the self-reflection in those dark days.

The 1900 Hurricane was such an event for a different U.S. government organization, the U.S. Weather Bureau, now the National Weather Service. That September 1900 hurricane killed at least 8,000 people, possibly as many as 12,000. The “Great Storm of 1900” still tops the list of deadliest US natural disasters. It has no official name—the Weather Bureau didn’t start naming hurricanes until 1950.

Some call that storm the “Great Galveston Hurricane” because most of the fatalities were on Galveston Island. Perhaps a sixth, maybe a fifth, of Galveston’s residents died. No one is sure exactly how many thousands died there because so many people were washed out to sea and presumed dead. After destroying Galveston, the 1900 hurricane killed more on its inland track north, including over 50 people in Canada.

The 1900 storm was what we would now call a Category 4 hurricane, not even the worst storm that nature can produce. But thousands died in just hours. Why?

It wasn’t just that era’s limited weather forecasting capability that failed Galveston residents. Yes, the US Weather Bureau was fairly new in 1900, having just become a civilian organization in the US Department of Agriculture in 1890 with transfers from the Army’s Signal Service. Weather forecasting was still more art than science then, but the new Weather Bureau had a lot of boots-on-the-ground experience. The US meteorologists predicted the large storm would hit Florida and issued evacuation recommendations there. However, Cuban meteorologists reported extensive storm damage in Cuba days before the storm was to make landfall in the US. Days before it hit Galveston, the Cubans told the US Weather Bureau that the storm was strengthening and heading for the Texas coast, not Florida.

In the wake of the Spanish-American War (1898), the US controlled Cuba. But the US Weather Bureau did not pass the Cuban predictions on to Texas residents because of bitter feelings and contempt for the Cubans’ perceived “lack of scientific expertise.” The head of the US Weather Bureau in Washington, Willis Moore, decreed that only he could authorize calling any storm a “hurricane.” In fact, the Cubans had more hurricane expertise than the US Weather Bureau. A US ship captain later reported the storm strengthening in the Gulf of Mexico, confirming the Cuban meteorologists’ projection of a westward path, in plenty of time to evacuate Galveston. But the US Weather Bureau still refused to issue evacuation orders to Galveston residents.

In Galveston, then the third richest city in the US, Dr. Isaac Cline and his brother Joseph staffed the local US Weather Bureau office. Dr. Cline had word of the brewing storm from the central office, but noted that the DC office did not seem too worried about it. He himself had downplayed the danger of hurricanes hitting Galveston for years. In fact, he was on record stating that it was impossible for a hurricane to hit Galveston. Perhaps local business leaders promoting the city and unwilling to pay for a proposed “sea wall” project had pressured him. High tides frequently flooded the streets and little came of that, so a little water in the streets did not alarm city residents. At that time, meteorologists thought the real danger of a hurricane was just the wind, as storm surge wasn’t well understood. Dr. Cline hoisted a single mariners’ warning flag up a flagpole on the tallest building in town the afternoon before the landfall. That flag was red with a black square in the center, the signal that a strong storm was approaching, but not a hurricane. Two such flags were required for a hurricane warning.

Joseph Cline was far more worried. He argued with Isaac for a hurricane warning. Isaac would not go against headquarters. He refused to raise the second flag to warn that the approaching storm was a hurricane. It wasn’t until the next morning that Isaac’s instruments and an unusual tide pattern made him realize that Joseph was right. But then it was too late to raise another flag. As the water rose, Dr. Cline raced his carriage along flooded streets on the seaward side of the island, personally imploring those souls outdoors watching the dramatic surf to shelter in fortified buildings. Dr. Cline’s efforts to warn others cost him dearly. He did not have time to get his family to stronger shelter. The storm surge soon covered the island. His wife was among the casualties when a drifting railroad trestle smashed their home.

Mixing politics and weather forecasting works no better than mixing politics and space exploration….People die when you do that, on the ground and in the sky.

I began writing this post during Winter Storm Fern, all the while marveling at both forecasting and thorough preparation. In rural communities, weather risk is the greatest part of economic risk, so improved weather forecasting is probably the greatest gift of our space program to rural America. Weather forecasters integrate satellite and space station data with info from 122 ground stations, 1,800 daily weather balloons, 245 ocean stations, 1250 ocean buoys, pilot reports, and decades of weather history to get ever-more accurate forecasts. At times, the US Air Force Hurricane Hunters and NASA’s WB-57 flying atmospheric science laboratories join the weather team. One of NASA’s three WB-57s suffered damage last week, landing on its belly after landing gear failed to deploy (BREAKING! NASA WB-57 Emergency Landing Without Wheels). I wonder if the aircraft was collecting data on the massive winter storm on that last flight. First flown in 1949, B-57s have been involved in weather reconnaissance and atmospheric research since 1964, first in the US Air Force and then with NASA. Those NASA B-57s are much older than the pilots who fly them. Here’s hoping NASA can restore this rare bird to flight and weather ops soon.

Virginia’s new governor—like many other governors in the path of this storm—declared a state of emergency days before Winter Storm Fern. The long-range forecast and the emergency declaration gave state agencies and infrastructure providers time to prepare. Many highway department crews sprayed roads with brine while others prepped snowplows. Utility crews spent that lead time clearing remaining branches over powerlines, and staged repair trucks at critical locations. Schools and churches announced closures. Airlines preemptively canceled over 10,000 flights—a very expensive move that suggests a great deal of certainty. But pilots are weather junkies and they have the best.

The rest of us used the time to stock pantries and cook food and test generators and fill fuel tanks and stage buckets of water to flush toilets. We checked on neighbors and hauled firewood for those who heat with wood, to make sure they have enough to get through the predicted extreme cold. We covered winter crops, hoping the cover hoops and fabric would hold up under the snow and ice load—and hoping the fabric would keep the plants alive through the unusual single-digit temperatures predicted. Those with livestock pre-positioned hay and broke ice on troughs and checked the trough heaters. We plugged in tractor block heaters and wedged spray cans of starting ether in cabs. Squirting starting ether into air intakes works a helluva lot better than prayers in getting engines started in single-digit temperatures. That hay won’t move unless that machine moves it. And every farmer who owns a blade mounted it on something that can move snow. Some would pick up extra cash plowing business parking lots.

When the snow and sleet were falling, we could—well, unless we have livestock--hunker down indoors and catch up on our paperwork. Or wax poetic on weather forecasting like yours truly. Weather junkies blessed with internet watched composite satellite and radar displays and infrared maps and precipitation maps—enabled by NASA and NOAA satellites and other NOAA sensors. I am a triple weather junkie, after years of farming, flying, and space-geeking.

We take it for granted now that we’ll have a week to prepare for a major storm, but I can remember when this kind of long-range weather forecasting was a pipedream. When I was in graduate school at Princeton University in the early 1980s, I had friends doing research at the university’s Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory. They were building weather prediction models and running them on what we thought was one of the world’s fastest supercomputers. “Our models are improving,” ran a typical conversation. “We got pretty close on that cold front last week. Now if only we could get those predictions done before the weather gets here!” We teased our colleagues with “How many days late this time?” and “Only three days late this time?” We had only two decades of satellite pictures of storms, and we had already forgotten that there was a time when we couldn’t see weather in the formation stage. Yet predicting weather more than a day or two in advance was still a meteorologist’s dream.

But meteorologists have a track record of dreaming big. The weather forecasting community started imagining what a view from above the clouds might be worth in World War 2. In 1946, some enterprising soul put a camera on the nose of a V-2 rocket confiscated from Germany to get the first photo of clouds from above. Thanks to the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA, now Defense ARPA or DARPA), the US was already designing satellites that could take pictures from orbit when the Soviets launched Sputnik in 1957. Seems that the military reconnaissance guys drank a lot of coffee with the meteorological guys, and that work found a big early payday in weather. Our Explorer-VII satellite carried an experimental weather-monitoring payload into space in 1959.

The first US operational weather satellite was the Television Infrared Observation Satellite (TIROS-1) launched in April 1960. It carried only two TV cameras (a wide-angle and a narrow-field) and video recorders, but that crude payload converted meteorology from a localized interpretation of ground instruments into a planetary science. It lasted only 78 days but transmitted over 19,000 pictures of cloud formations and storms (see the first below).

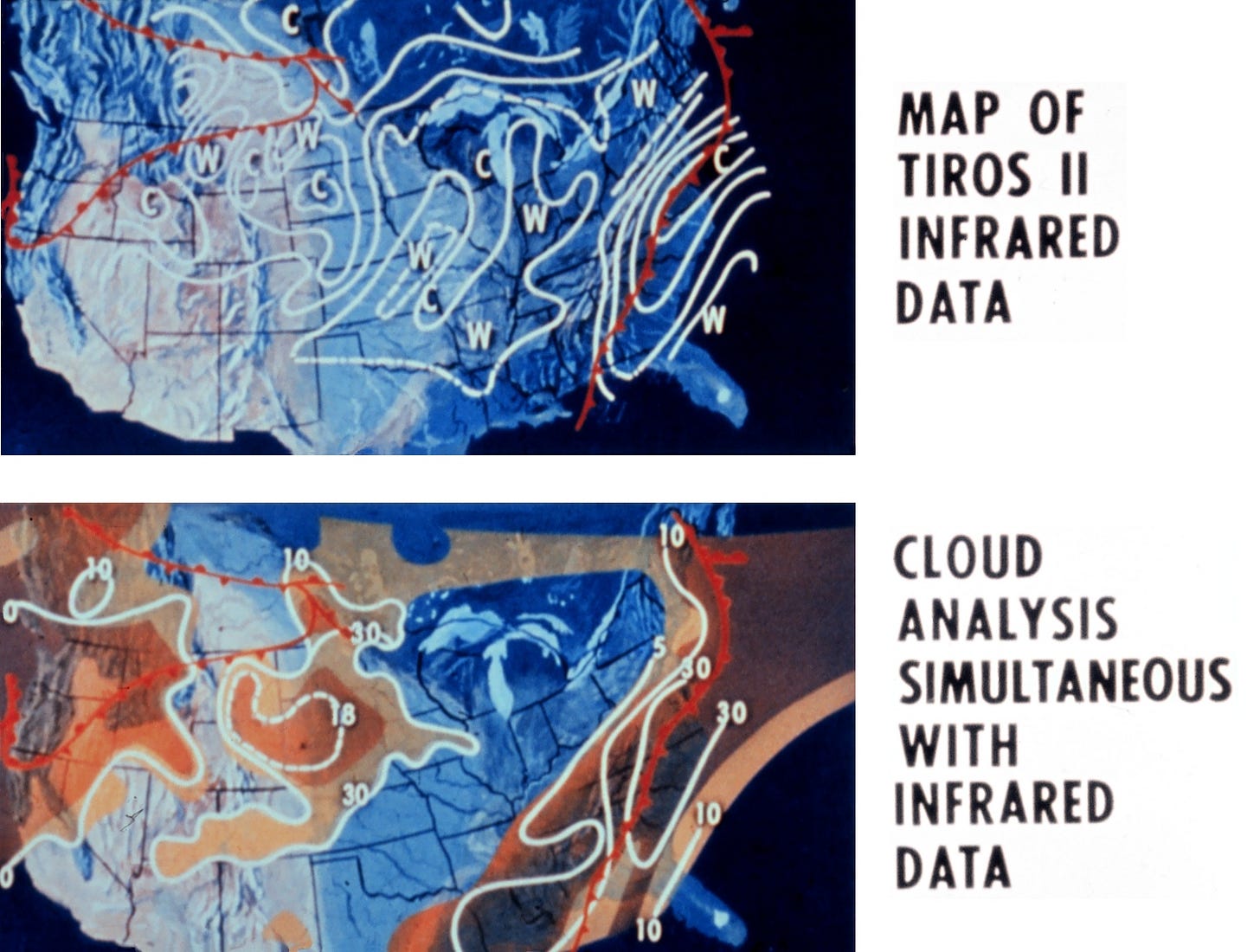

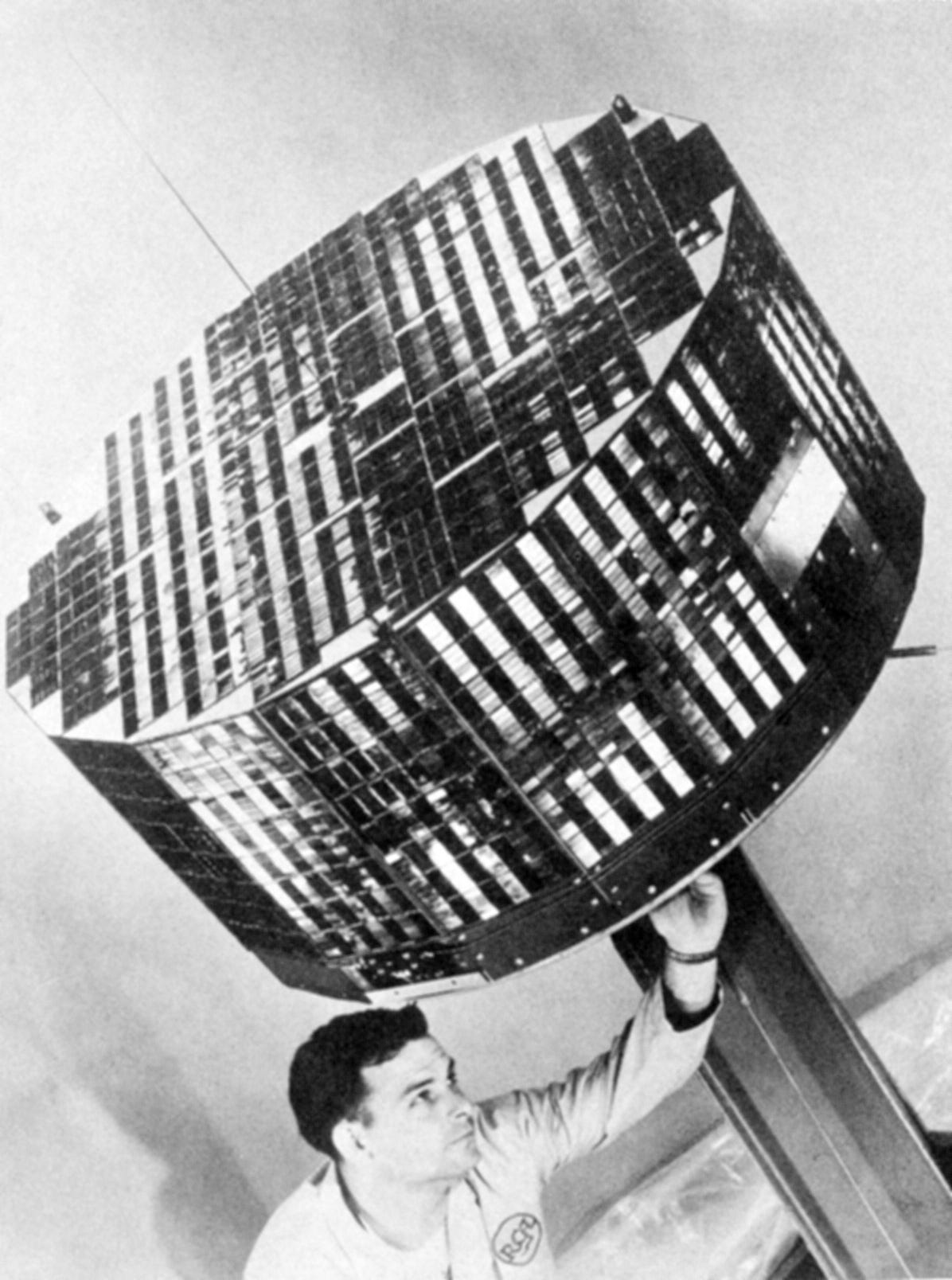

NASA launched TIROS-2 (photo below) in November 1960 to add infrared capability (radiometers), which made frontal boundaries and ice visible (see a sample product below). The satellites were only part of this effort, because NASA had to build receiving stations and data distribution and analysis to make them useful to line meteorologists. The TIROS program lasted decades and pushed our ability to put satellites in polar orbit.

A parallel program, the Nimbus weather satellites, began in 1964 with the purpose of advancing weather instrument technology. Seven Nimbus satellites carried 33 innovative new instruments into polar, sun-synchronous orbits from 1964 to 1978. Nimbus-3 (1969) enabled early storm warnings with its “Sounder” vertical measurements of temperature, moisture, and water vapor across Earth. Previously, that capability required balloons or aircraft—severely limiting coverage over oceans where the largest storms form. TIROS-N (1978) took that capability to space because it was enhanced with microwave sounding, enabling the satellite to see “through” clouds. It also carried payloads that laid the groundwork for satellite navigation systems.

NOAA was formed in 1970. It consolidated the US Weather Bureau (renamed the National Weather Service) with the US Coast and Geodetic Survey (commissioned by President Thomas Jefferson in 1807), the Environmental Science Services Administration (ESSA, in the Department of Commerce), Bureau of Commercial Fisheries and other fishery programs (in the Department of Interior), Marine Minerals (Interior), and oceanographic and lake groups from the US Navy, US Army, and National Science Foundation. At one point, putting the US Coast Guard in NOAA got serious consideration. But guys on armed boats and scientists struck some as strange bedfellows.

Reorganization Plan No. 4 of 1970 (5 U.S.C. app.) detailed the NOAA and EPA creation. In it, President Nixon provided these reasons for the formation of NOAA:

“Drawing these activities together into a single agency would make possible a balanced Federal program to improve our understanding of the resources of the sea, and permit their development and use while guarding against the sort of thoughtless exploitation that in the past laid waste to so many of our precious natural assets. It would make possible a consolidated program for achieving a more comprehensive understanding of oceanic and atmospheric phenomena, which so greatly affect our lives and activities. It would facilitate the cooperation between public and private interests that can best serve the interests of all.”

Exactly where NOAA would be on the government org chart had just been an epic struggle in the Nixon Administration. Three camps formed to advocate for NOAA as (1) independent agency; (2) part of the Department of the Interior; or (3) part of the Department of Commerce. Congressional overload ruled out making NOAA an independent agency. Creating the Environmental Protection Administration (EPA) as an independent agency completely consumed Congress’ capacity for major reorganizations that year. Choosing between Commerce and Interior as NOAA’s home was easier, just a matter of an Executive Order with Congress having a ninety-day veto window.

Initially, it looked like the decision would go in Interior’s favor, and the President’s final decision to put NOAA in Commerce surprised many. Urban legend has it that NOAA was put in Commerce instead of Interior because President Nixon and his Interior Secretary (Walter Hickel) began feuding over the Vietnam War. It seems that Mr. Hickel started listening to the people protesting the Vietnam War as he ran their protest gauntlet to work every day. They eventually won him over. Or perhaps he was just tired of troops stationed in and around his office buildings. He implored the President to “listen to the youth” to defuse the standoffs. Mr. Hinkel’s heartfelt letter to the President was leaked to the press; the bad coverage made a lot of White House people mad. President Nixon was especially mad.

Steven Schanes, Special Assistant to the Secretary of Commerce for Policy Development, had the unenviable job of creating the new agency inside Commerce, despite his personal opinion that it should be an independent agency or perhaps Interior might be a better fit. The scientific community—especially the marine research community—had lobbied hard to put NOAA in Interior, saying that “Commerce’s purpose is to sell fish” while Interior’s purpose is to “protect fish.” In his memoir, Mr. Schanes acknowledged Mr. Hinkel’s letter as a factor in the President’s decision. But he also relates that the President thought (1) Commerce was better managed than Interior and (2) integrating NOAA into Commerce would be the least organizational upheaval because they already had a major piece of the pie. That piece, the Environmental Science Services Administration, would become about 70% of the new NOAA in personnel and budget. Mr. Schane also related that the President quickly accepted Commerce’s choice to lead the new agency (meteorologist Dr. Robert White, then head of the ESSA). Nixon’s staff objected to Dr. White’s promotion because he was a Democrat and his brother Theodore White had written a book very critical of the President. Nixon just asked, “Is he the best one for the job?” and shut down all objections when the Commerce Secretary affirmed that. Seems Mr. Nixon was not all political.

Unfortunately, NOAA has been underfunded since its birth, considering its mission. Partnering with NASA and Department of Defense (DoD) for satellite development helped. After NOAA was formed, the TIROS satellites got a NOAA designation along with their TIROS legacy name. The final TIROS satellite (TIROS-N-Prime or NOAA-19) launched in 2009 and was only decommissioned last August.

The first Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellites (GOES-1) launched in 1975. The GOES series—joint work of NOAA and NASA—differed from its polar-orbiting TIROS and Nimbus predecessors by spending their entire operational lives over a fixed point on the earth’s surface. The GOES series provides near real-time data critical for weather forecasting and severe hazards including hurricanes. GOES-7 introduced NOAA’s Search and Rescue Satellite-Aided Tracking (SARSAT) to quickly locate distress beacons. If you carry a Personal Locator Beacon (PLB) for emergencies, you are relying on GOES-7 and SARSAT to get out of a jam.

Fifty years later, we are up to GOES-19, declared operational in September 2024. The GOES satellites can monitor lightning now. And track wildfire in real time, assisting firefighters and keeping them out of the fires’ path. The next generation of GOES is the Geostationary Extended Observations (GeoXO). These satellites will increase our advance warning for drought and flooding, as well as improve detection of lightning, fire, smoke, dust, and volcanic ash. First launch is planned for 2032, funding permitting. I envision myself in 2040 in my rocking chair, hypnotized by GeoXO satellite feeds and regaling my unlucky nursing home roommate with soil moisture and lightning data.

Incidentally, the GOES satellites also monitor “space weather”—the electromagnetic storms that interfere with space-based electronics, our utility grid, communications systems, and global positioning system (GPS) signals. Not as important as weather and climate prediction, Satellite-based navigation systems have still been changing agriculture. GPS is now the time source that synchronizes critical systems including our power grid. GPS guides tractors to reduce soil compaction from heavy machinery. Farmers also rely on GPS for precision planting systems. Some farmers rely on GPS to steer planters and harvesters 24 hours a day. Those systems operate in the dark to take advantage of short planting and harvesting windows. So, now farmers follow space weather. May 2024’s G5 solar flare gave us auroras across the lower 48—and farmers reported that “the tractors acted like they were demon-possessed.” Crooked rows and even “doughnuts” in the field translated into yield losses with fertilizer and seed mismatches. Then at harvest, machines could not perfectly align with rows planted by those rogue tractors.

All of the data from these satellites is available free of charge to anyone. Our tax dollars put those satellites up there and built the communications links and data centers. We’ve also paid for much data analysis, converting raw data into products that we can use to make decisions ranging from what to wear today to whether to go out at all or run like hell. Aviators, farmers, mariners, military planners, school administrators, emergency response managers, government officials, and the multitudes of our hard-working neighbors now make informed decisions about what they can do next. Emergency response managers use pre-position rescue and recovery teams. If you were also in the path of Winter Storm Fern, you probably saw utility trucks located along power lines before this week’s storm hit. Thirty states and 230 million people took a turn in Fern’s temperature and precipitation extremes and over 50 of them did not live to see the other side. Over a million households lost power and some of them are still in the dark today (February 2nd, 2026).

The ice accumulation here in south central Virginia was closer to the minimum than to the maximum predicted. It was not enough to leave me in the dark. My darkest thoughts were for how it’s still hard to pinpoint what will happen at a specific location near a coast when two very different air masses battle for dominance. In Nashville, TN, ice accumulation forecast was spot-on—unfortunately! My nephew there was without power for a week. The photos he sent of the ice-encrusted tree branches laying in the streets by completely denuded trees left me thinking that pre-positioned equipment and crews shortened that power outage from what it might have been.

While we still have tragic loss of life in major storms, it’s much lower due to this amazing earth data collection infrastructure and dedicated people turning this raw data into information we use daily. The reduction in death toll is all the more impressive considering the nearly five-fold increase in US population since 1900. Our population is even more exposed to hurricane risk, as over half of US residents live within 50 miles of a coastline. A surprising number of people live below sea-level behind levees. Many more live below the level of a storm surge from a direct hit of a category. They need a forecast to inform a decision to evacuate.

Farmers need weather forecasts for more than personal safety. We need weather forecasts to survive economically. We need mid-range forecasts for decisions like “When will the soil be warm enough for seeds to germinate?” We need long-term forecasts to help us with decisions like “Will we get enough rain this season for this seed, or should I try a different variety with better drought tolerance?” and “How many calves can I realistically carry over next winter with this summer’s rainfall?”

The groundhog with the unprintable name—the one who destroyed my butternut squash crop last year—saw his shadow on the frozen snow this sunny morning. But I already knew we will have six more weeks of winter. NOAA told us that we’ll be seeing several more of these cold air masses this month, keeping temperatures below average.

Unfortunately, our current administration has begun eliminating some long-range weather forecast products because “climate” has become a dirty word. NOAA has been accused of being the source of “climate alarmism.” Climate.Gov is gone, but fortunately some of its content has been preserved on lower internet rungs, so we won’t have to rely completely on that #$@%*& groundhog to schedule spring planting. In my next newsletter, I’ll explore what the attack on NOAA means for farmers and everyone else’s dinner plate. And whether weather will continue to be free to the public.

But maybe I’ll let that fuzzy squash-wrecker live a little longer, just in case he becomes my only source for “climate” prediction.

References:

A Timeline of Extreme Storms Throughout U.S. History

The 1900 Storm - Galveston Historical Foundation

1900 Galveston Hurricane Destroys City

How many people die from extreme heat in the US? | USAFacts

Weather Related Fatality and Injury Statistics

Temperature Data:

https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/monitoring/climate-at-a-glance/

Weather Satellite History:

50th Anniversary of the TIROS Satellite - NASA Science

TIROS-2 - Wikipedia (includes Universal Newsreel with launch)

Television Infrared Observation Satellite - Wikipedia

Nimbus Satellites - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics

The Creation of NOAA:

The Battle for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) | Steven Eli Schanes

REORGANIZATION PLAN NO. 3 OF 1970

Public Weather Sources:

National Hurricane Center: nhc.noaa.gov

Homepage | NOAA / NWS Space Weather Prediction Center

Category 4 | NHC Storm Surge Risk Maps

Discontinued Public Weather:

Recent Conditions for Crops - Weekly Publication | NOAA Climate.gov

Thanks for the well-researched and wonderfully-written essay on the history of our National Weather Service. I had forgotten about the Galveston Storm of 1900, but it's sad to discover that we ignored the advice of the Cuban weather observers. They know a thing or two about hurricanes!