Is Your Steak at Stake?

Digesting grass is really, really hard.

COP28 was very much in the news through this past Christmas season. “COP28” is short for the “28th Conference of the Parties of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.” Wow, no wonder everyone just calls it COP28. Reports on this year’s conference included a lot of comments like “agriculture causes a third of all greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.” Given that COP28 took place in a country—Dubai—where the number one product is oil, not food, this spotlight on agriculture GHG emissions does not surprise me. Nor does this year’s efforts to wring commitments to reduce agriculture-related emissions out of the attendees.

Whether you believe that human activity is causing the increase in weather extremes may depend on what media you consume; however, it is pretty hard to make a case in farm country that the weather is not changing at all. Farmers spend a LOT of time looking at weather. Probably more than any profession besides weather forecasters. Keeping the farm depends on a farmer planning for the weather, predicting the weather, working in the weather, and weathering the weather when the weather isn’t what said farmer hoped for.

And now, farmers have to figure out how to weather being blamed for the change in weather.

A Reuters article quoted the “global leader of food practice” at the World Wildlife Fund (Joao Campari) as saying "Business as usual food systems would use nearly the whole carbon budget for a 2-degree Celsius world. We need to implement food systems approaches throughout COP28.” Ouch. Well, the World Wildlife Fund is not exactly known for advocacy of agriculture. Or people. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)—a somewhat more neutral organization—says that GHG emissions from agriculture are probably 31% of the total of human-made GHG. Not quite a third, but big enough to prompt this farmgirl to dig deeper in this manure pile.

One problem is what the definition of “food system” and “agriculture” are. A Wikipedia article cites five scholarly sources to conclude that “The agriculture, forestry, and land use sector contribute[s] between 13% and 21% of global greenhouse gas emission.” But then the same article goes on to say that domestic livestock emit 14.5% of all “anthropogenic” (human-caused) GHG. Hmmm. Not sure I follow their math. Still, evidence is accumulating that domestic livestock are producing a lot of GHG. A 2019 University of California-Davis study showed that a single Holstien could “burp” 220 pounds of methane in a single year. We owe that poor girl a nice green-pasture retirement somewhere, because apparently she spent the whole year with her head in a bubble, cooperating with those scientists. Methane traps 28 times more heat in our atmosphere than pure carbon dioxide does, and it takes about a dozen years for it to break down naturally into carbon dioxide. No wonder cows are getting a lot of attention at climate conferences.

Some US media outlets talk of a conspiracy to take away your steaks while others are bent on serving up a side of guilt with your burger. Grocery stores are trying to convince you to pay more for “environmentally-sustainable” food. So, a deep dive into food production impacts on climate feels timely. But which of the stories shouting at you from the grocery store shelves or media outlets should you heed?

I think we can agree that we all have to eat to live. Food requires energy to produce, move, store, and prepare. Energy production and usage has emissions. Food production emits greenhouse gases, including methane. And as population increases, those emissions increase proportionally. As people boost themselves up from subsistence, graduating from rice and bread to meat for dinner, those emissions increase exponentially. The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization projects a 70% increase in beef and dairy consumption over the next thirty years. But those of you feeling guilty might pause the draconian no-beef New Years resolutions until we cover the tradeoffs. There’s a lot you can do to reduce greenhouse gas emissions short of giving up steak forever.

I am biased observer. Our family’s very first livestock venture in 1965 on Excalibur Farms was a small herd of Angus heifers. I was six years old. I still remember watching them unloading from a truck, hoping that a pony would get off with them. A neighboring cattle breeder had tried closing the sale on his heifers by bribery. He promised to give me the pony I was petting in his barnyard if my parents bought heifers from him. I don’t recall where those first heifers came from that day, but I do recall my disappointment, looking at the empty truck and no pony. But once I got over that—my grandfather helped by finding a Shetland pony with a cute black colt somewhere—I decided that cows were cool. Good thing, too: my father soon discovered he had a squeamish streak. He delegated livestock care to my mother while he learned to grow corn. “If it has roots, it’s mine. If it has legs, it’s yours,” he told Mom. Being Mom’s shadow, that made livestock my job, also. Dad got very good at growing corn and Mom got very good at breeding cattle. Within a couple of years, we were filling the old dairy-cow feedlot with steers to be finished for beef. We had a thousand-pound freezer to hold any cow that goofed up calving, too, as the punishment for that crime was an invitation to dinner. Our operation expanded to include pigs (my grandfather’s favorite) and egg-laying chickens (my older brother’s favorite) for a time. Two decades in, however, the pigs and chickens were memories and sheep outnumbered cows on our farm. As Dad lost the energy to grow corn, he became fascinated with sheep. But Mom still got stuck with the messy parts of the sheep operation.

Along the way, I learned what humanity’s fundamental food problem is: Getting the protein out of grass is hard! Nature grows a lot more grass than vegetables. We humans can’t get enough nutrients out of cellulose to live. We are predators because we need our prey to digest those plants for us and turn them into something that we can digest. We domesticated reindeer and cows and sheep and goats because they are really good at digesting cellulose and turning it into something we humans can digest much more easily. These animals have the added bonus of storing that protein on the hoof in a non-perishable package until we are hungry, which was a lot more important before we invented freezers. Ask a cattleman or shepherd east of the Mississippi River what he does for a living, and you will often hear “I’m a grass farmer.” Grass in this context is a loose term for all the plants that whatever animal you are grazing will eat. The technical term is forage. Easterners grow really good forage, which they sell on the hoof. West of the Mississippi, cattlemen call themselves “ranchers” because they usually have enough space to let nature do the work of growing forage. Many young livestock growers who graze their livestock on land they don’t own—all too common today given the price of land—have resurrected a Victorian term for their business model: “graziers.”

Reindeer and cows and sheep and goats do the magic of extracting protein from forage by fermentation. They break down cellulose in a special chamber in their stomachs, which old-timers called the paunch but we now call the rumen. Hence the name ruminants. Deer, moose, antelope, giraffes, buffalo, and aurochs also have rumens, in case you still insist on chasing your dinner around the woods instead of the grocery store. Aurochs, you ask? That’s the wild Eurasian ancestor of the modern domesticated cow, thought to be extinct but recently brought back in Europe. Wikipedia says there are about 200 species of ruminants in the world.

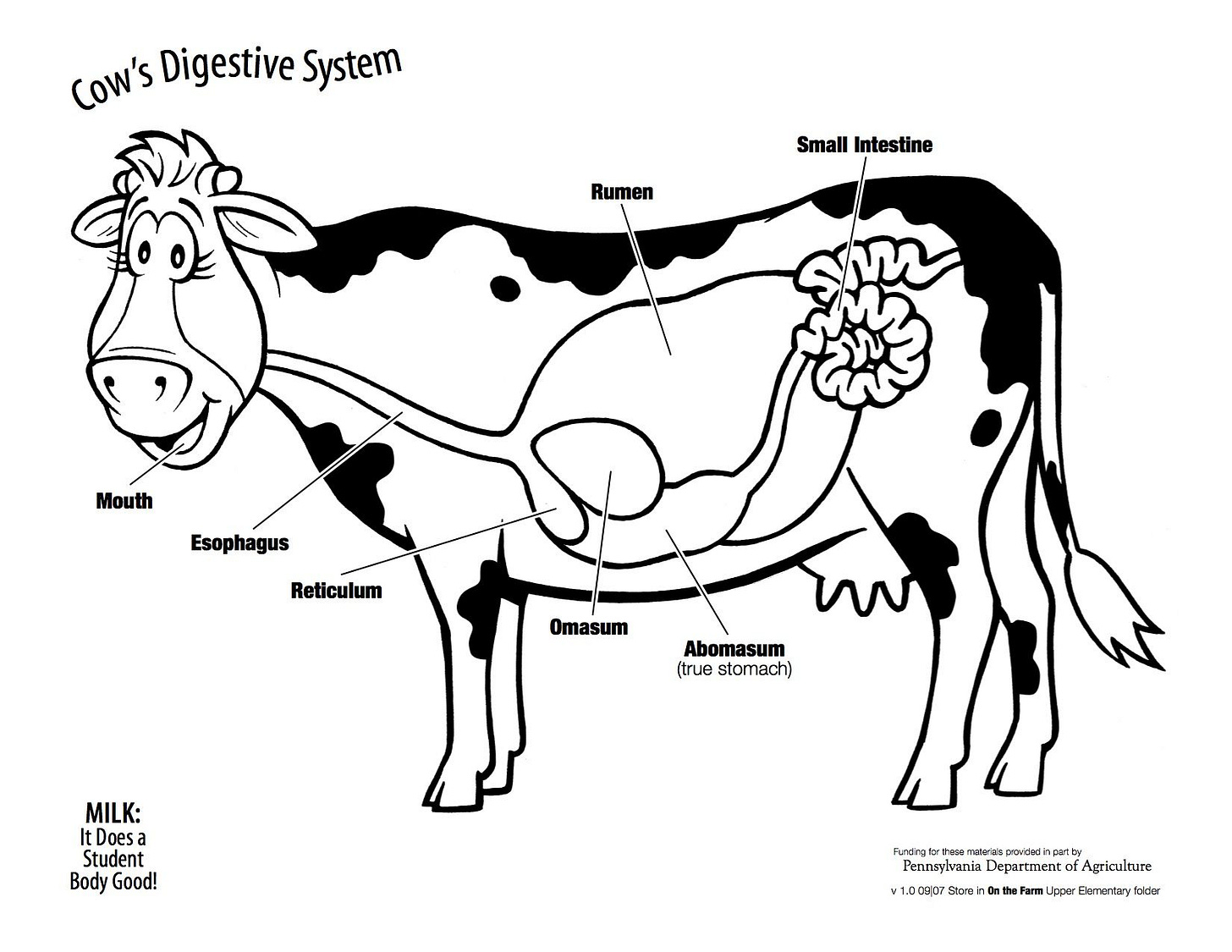

Technically, the rumen is not a separate organ but the front end of a long, long multi-chambered stomach. There are actually four chambers in a ruminant’s stomach—not four stomachs in a ruminant. The “four stomachs” is a very old conception of this very complicated organ. The first two chambers—the rumen and its next-door neighbor the reticulum—work together as the fermentation apparatus to tease the nutrients out of that stubborn forage. This is why ruminants are in the “foregut” fermenter class. Most of the fermentation takes place upfront in the rumen. The rumen is huge: it’s the reason ruminants have such round mid-sections. The forage-eating animal keeps that chamber at a nice warm 100-108 degrees Fahrenheit and a pH between 6.0 and 6.4. Compare that with the pH of our own stomachs, which hovers around 1.5! Recall that pH goes from 0 on the acid side to 14 on the base side, with pH of 7 being neutral. The ruminant’s higher pH is welcomes microbes that break the cellulose down into nutrients for the animal—and methane. These bugs are (surprise!) called methanogens.

To start the cellulose digestion process, the animal chews the forage into a “cud” and sends it down into the rumen with lots of saliva for fermentation. Later, when the animal is relaxing, perhaps chillin’ in the shade, it brings solids that haven’t broken down in the rumen yet back up into their mouth and chews them again. Farmers call this “chewing the cud.” An important aspect of chewing the cud is mixing in more saliva to help the fermentation chemistry. Saliva is a natural antacid. Our own saliva’s pH is about neutral, neither acid nor base. A ruminant’s saliva has a base pH: between 8.1 and 8.9. Injecting more saliva via chewing the cud is the way the animal keeps the rumen’s pH high enough for fermenting the cellulose.

Perhaps because of the relaxed and thoughtful expression the average cow has while chewing her cud, the expression applied to humans has come to mean “to think slowly and carefully about something” (Cambridge Dictionary). The word "ruminant" comes from the Latin ruminare, which means "to chew over again.” Perhaps you’ve told someone that you needed time to “ruminate” on a proposal before you could decide on accepting it. I wonder how many people who use that expression realize what is literally being chewed and how many times. The other culturally-important detail about the cud comes from Leviticus 11:3-8: to be kosher, an animal must chew the cud as well as have a completely split hoof. These kosher restrictions have theological roots.

The press made much of a cud-chewing fact during this past Christmas season. In the northern latitudes, reindeer have to digest most of the year’s food in a few short months of very long days. They have developed a fascinating time hack for this: reindeer chew their cud while sleeping. Who knew? I wonder if they also chew their cuds on the housetop while waiting for Santa to leave toys and coal.

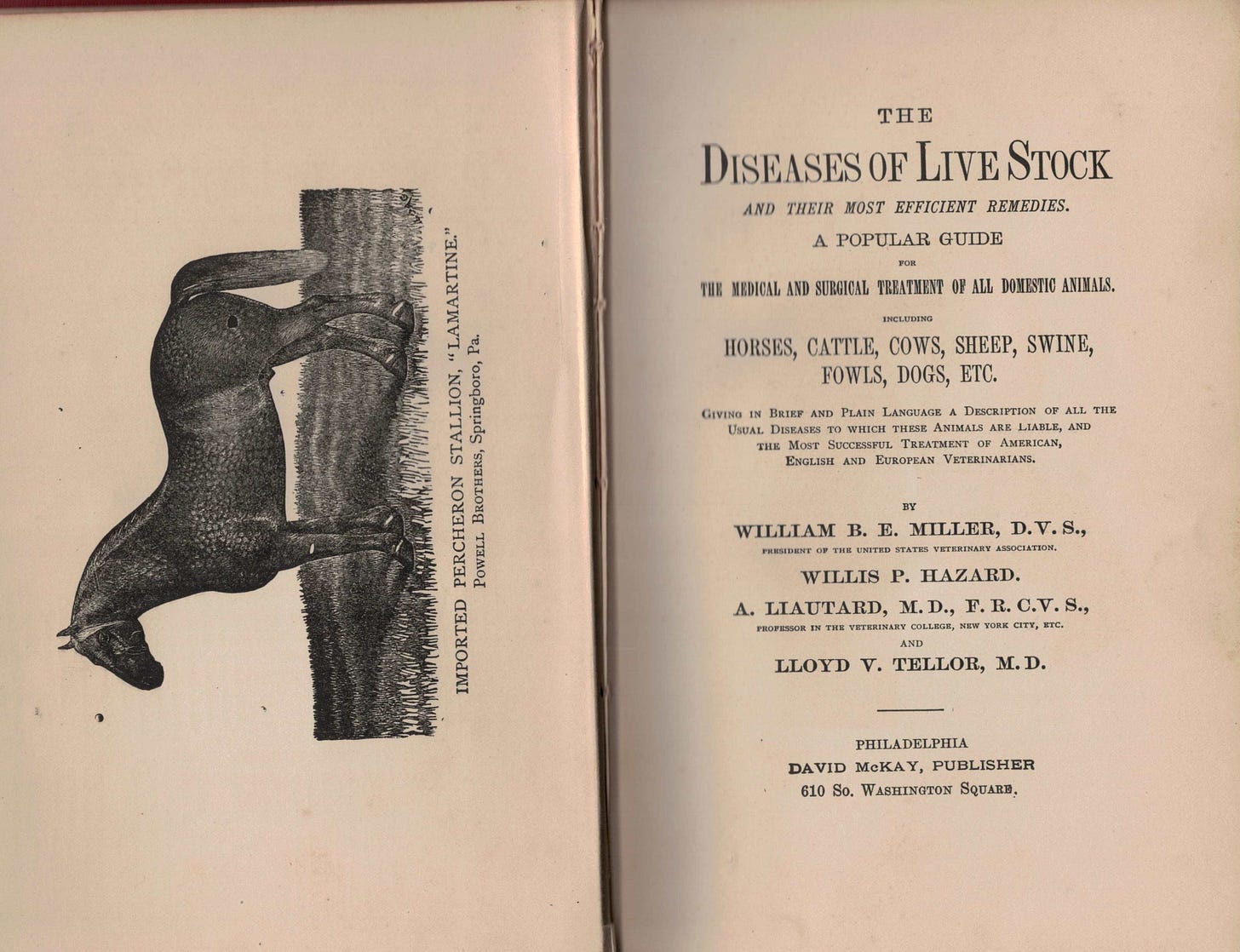

But back to chasing that forage through our neighborhood ruminant. The reticulum—the number two stomach compartment—helps the rumen with fermentation by filtering out the large incompletely-fermented cud and sending that back for another round. It is often called the “honeycomb” (and it looks like one), but other very old terms are “bonnet” and “kings-hood” (still trying to figure that one out). You won’t find these terms connected with ruminant stomachs on the internet. I found them in a book that I bought at an antique shop for a quarter when I was ten years old: Diseases of Livestock and Their Most Efficient Remedies, by Miller and Tellor, published in 1890. It was a momentous find for a kid who wanted to be a large-animal vet. Our farm vet Dr. Matt [Graves] teased me unmercifully about this book, but we both had a lot of fun evaluating medical progress. I rediscovered this treasure last week when sorting through over five decades of family stuff from Excalibur’s farmhouse. Curiously, the page on “Hoven-Blown”—the old name for impacted rumen—was book-marked by a newspaper clipping of Princess Anne galloping her horse Goodwill during her 1976 Olympic appearance. Perhaps I kept that picture as a reminder that Princess Anne got back on that horse after a horrific fall and concussion and completed that Olympic course. The connection between the Princess Royal and that particular cattle ailment escapes me now, but I note the 1890 vet book refers to four distinct stomachs, not chambers in one stomach. At times the authors struggled to attribute various conditions to one stomach or another, a clue that they were really working together closely.

One old term for the third chamber (omasum) is “butcher’s Bible” because its interior surface looks like the pages of a book. There were times and places where the Bible was the only book many farmers had to read. The Wesley brothers’ Methodist Societies got around bans on working class people having books by teaching children to read using Bibles in Sunday School. The cow’s “Bible” controls the size of what gets to the last chamber as well as being the place the animal absorbs some of the fatty acids from this process. I am still pondering possible theological meanings of this. The veterinarians of yesteryear used the terms “psalterium” (a fancy name for the Book of Psalms) or “manyplies” for this chamber, possibly to show that they had been to a real school. A trip through the cow’s digestive tract from the grass’ perspective helps you understand those old names. Of course, you can find this virtual trip on the internet. Check out these Bing Videos.

The last chamber (the abomasum) is the “true stomach,” similar to our own stomach. It’s where the cow absorbs most of the proteins and other nutrients freed from the grass in the first three compartments. Farmers where I grew up called that stomach the “maw” or “rennet” but apparently butchers and cooks call it the “reed.”

Whoa—do cooks really have special names for parts of ruminant stomachs? Most Americans are a couple of generations removed from the “eat everything but the moo” days, but the foodies among you may have eaten some of this fermentation apparatus. That honeycomb? When a cook slices it up for dinner, it’s tripe. If you eat menudo on Sunday morning in central Texas to chase away your hangover from Saturday night out on the town, you’ve eaten some cow’s reticulum. If you are fond of Dim Sum (ngau pak yip), you have probably eaten the butcher’s Bible. In Scotland, the national dish of Haggis was traditionally cooked in the animal’s stomach—but you won’t find true Haggis in the US unless you butcher the animal and make it yourself from scratch. US food safety regulations ban the sale of some Haggis ingredients.

Do you like cheese? The complex mix of enzymes traditionally used to make cheese—also called “rennet”—comes from the abomasum, that true stomach. For millennia, the most prized rennet enzymes have come from calves slaughtered for veal, because those calves have been fed only milk. The rennet enzymes curdle the milk in the calves’ stomach so that it is easier to digest. The calves’ digestive enzymes change with age and diet, thus changing the type of cheese formed with the rennet harvested from the animal’s stomach. You can now buy this on Amazon, to make your own cheese.

Every now and then, I have to pause and marvel at the complex web of our food system, developed over millennia, nearly all before refrigeration. Imagine how humanity learned to exploit all the corners of an already-complex ecosystem. Imagine how our ancestors learned to create easily-stored delicacies like cheese by imitating what goes on in an animal’s stomach.

Fortunately for the cheese-lovers who are horrified by the idea of killing young animals for veal and rennet, Pfizer transplanted the genes responsible for producing the rennet enzymes into microbes. Yes, the same company that brought us an mRNA coronavirus vaccine during the pandemic. These microbes produce a very consistent quality rennen, the ingredient in rennet important to cheese makers, also known as chymosin B. This microbe product is known as fermentation-produced chymosin (FPC). Approved by the FDA in 1988, it’s the “rennet” used in over 90% of the cheese on the market today. No, the FPC does not contain any “GMO” material—that is filtered out. And now you also have an inkling of why making cheese for sale requires extensive education and a special license. And if you are opposed to both genetic engineering and killing animals for food, you need to stop eating cheese. Sorry about that.

For everyone else, trading your steak for a nice hunk of cheese may not reduce methane emissions much, unfortunately. There’s a ruminant somewhere in the cheese production process, digesting forage and burping. Most likely cows, but cheese lovers are keeping sheep or goats or perhaps even yaks in clover (or some such forage). While beef production is blamed for 25% of the agriculture system’s greenhouse gas emissions, dairy is being blamed for 8%. That’s 9% of total greenhouse gas emissions for beef and about 3% for dairy. Dairy cows ruminate in the process of converting forage into milk. So, it's not just steak at stake here.

Every cow, sheep, goat, or reindeer has a phenomenal bio-reactor inside of it, converting plants to protein that we in turn can easily digest. Unfortunately, just like a bioreactor you might build to intentionally produce methane from organic material, the ruminant’s bioreactor produces methane. For the ruminant, it’s an unwanted byproduct. They are in this for the fats and proteins. So they burp the methane out as a waste product. This is called “enteric methane emissions.” There was a time when this was a good thing, because our planet needed greenhouse gases to keep it warm enough for mammalian life. Win-win. But now that some of that mammalian life (us!) has found many creative ways to make or release large amounts of GHG into the atmosphere, not so much.

Some of you are wondering: what about flatulence, the emissions from the other end of the animal? Turns out that’s minor compared to the front-end emissions. 90-95% of livestock methane emissions come from burping—the fancy word is eructation—and only 5-10% come from flatulence and livestock waste storage. The non-farmers are dying to ask a question at this point. No, the barn is not filled with a racket from burping critters. Ruminants have very quiet burps.

Sheep are also ruminants, but lamb has a lower per-serving carbon footprint than beef. Sheep require only 60% of the forage per pound of meat that cattle require. Sheep are also better at offsetting their enteric methane emissions by enhancing carbon sequestration in soil. Spending a large chunk of my life raising sheep biases me just a bit but having lamb for dinner instead of steak sounds like a great climate-change mitigation plan to me.

You might also try those tasty Mexican cabrito (goat) dishes, as goats are also more efficient than cattle at converting feed to meat. I personally have a love-hate relationship with the little rascal-Houdini’s, as they are nearly impossible to fence in and will eat anything. But the “eating anything” part can be useful, because goats will eat a lot of invasive species that a cow won’t touch. And even some the sheep won’t eat.

What about moving away from eating ruminants altogether? Denmark passed a law in 2021 requiring its agriculture sector to cut GHG emissions by 55% from the 1990 level by 2030. Unfortunately, Danish dairy and beef industries have been on a growth track since 1990—greatly encouraged by their government(!)—which means that meeting this target will require a per-cow methane-reduction miracle. This year, Denmark is considering a large tax on cattle to “encourage” Danish farmers to switch to crops and pork production. Small wonder European farmers are blocking traffic in cities with their tractors.

Pigs and people have something in common: not only are we both omnivores, but neither of us have rumens. We are both “monogastric.” We both have single-chambered stomachs where we wrest proteins out of protein-rich food with very acidic enzymes. The interesting microbiome shenanigans needed to digest most plant matter happen post-stomach in our intestines. This is “hindgut fermentation.” We don’t burp out methane. We do release some methane, but we won’t get into the how here in polite company. Most of our bio methane contribution comes from processing our own waste outside of our bodies.

Some herbivores (horses, rabbits, and our arch-nemesis the rat) don’t have rumens either, so how about eating them? These hindgut fermenters have a very large “large intestine,” and an area called a caecum that contains a microbiome suited to breaking down cellulose. I can’t see those becoming our choices at Fourth of July cookouts anytime soon. We hate the idea of eating Trigger and Blaze in the US. In fact, we have banned horse slaughtering here. Rats totally freak us out. Rabbits, not so much, but when did you last see rabbit in the grocery store? If you have seen that recently, it says a lot about where you shop.

How about poultry? Chickens and turkeys are not ruminants. They require a lot less food per pound of human-edible protein than cows do. That translates into a lower carbon footprint in their feed production, in addition to less GHG produced while they digest that feed. According to Consumer Ecology Footprints, a four-ounce serving of turkey has only one-fifth the carbon footprint as four ounces of beef. So there’s a little serendipity in our holiday turkey traditions. But Santa may need to rethink his reliance on reindeer for toy transport. Up on the housetop, reindeer pause—and burp methane.

Even though the world demand for meat from ruminants is increasing—mostly due to the increase of human population—the number of ruminants in the world has not increased in lockstep with the human population increase. This is due to two factors.

First, genetic and nutrition improvements have greatly increased the amount of meat yielded from each domestic animal. US cattlemen and women produce 18% of the world’s beef with only 6% of the world’s cattle. (Buy American Beef… oops, that’s another newsletter.)

Second, the population of wild ruminants in the world prior to industrialization was huge. Perhaps 165 million wild ruminants ate grass in North America alone prior to Columbus. That population has decreased while the domestic ruminant population has increased. Some researchers say that bison numbers may have been as high as 60 million. Perhaps over 100 million other wild ruminants typically lived in what is now the US. Bison numbers are down to a half-million today, and that’s after intensive recovery efforts brought them back from near extinction. Other wild ruminant numbers are increasing but are still less than half of the pre-Columbian numbers. Bambi is the only big winner on the wild ruminant side. Today, 25-35 million white-tail deer roam the US. They are destroying our forest ecosystem as well as shrubs and gardens. So, eating more venison is a climate win-win. That dinner choice opens up some space for the endangered deer species.

About 92 million cows, 5.2 million sheep, and 2.5 million goats lived in the US in 2022. That’s about 100 million domestic ruminants. I have not yet found ruminant population growth for the entire world, but I am starting to get the idea that the much bigger population change between then and now is the human population, not the ruminant population. In 1800, humans numbered about 1 billion. Today, we are closing in on 8 billion. Methane in our atmosphere has doubled. Maybe we need to take a harder look at our own GHG emissions.

We can start with reducing food waste. A typical US household of four spends $1500 per year on food that ends up in the trash. To quote the USDA/EPA draft National Strategy for Reducing Food Waste and Loss and Recycling Organics, “producing, grading, packing, processing, distributing, retailing, preparing and disposing of the amount of food that is currently wasted annually in the United States contributes greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions equivalent to those of 60 coal-fired power plants and requires enough water and energy to supply more than 50 million homes each year.” This draft strategy was released December 5th, 2023, for public comment, with over 10,000 comments received as of today. Both the strategy and comments are an interesting read (links below). Here’s one of my favorite comments, submitted by private citizen Marty Green:

Tons of food waste could be prevented by educating the public that food does not need to be thrown away on the date stamped on the carton. My children and grandchildren have been brainwashed to believe they will suffer dire consequences if they eat anything with an "expired" date. To them, it does not matter if the stamp says "use by," "best by," "sell by," or "expires." An entire generation has been misled into throwing out heaps of food that is perfectly good just because there is a date stamp on the package. Maybes my kids will come to dinner again without being suspicious that I've prepared "expired" food.”

Another favorite comment comes from the National Potato Council, whose CEO explains that the majority of food thrown away by children in school cafeterias is vegetables other than potatoes, so having potatoes as one of the vegetable-and-fruit choices at every school meal will reduce school food waste and might even encourage children to eat more vegetables. I was surprised to learn that current school lunch regulations limit the number of meals per week at which potatoes can be served.

Sadly, nearly a quarter of the beef we buy in the US is never eaten! One of every four cows slaughtered dies for naught. Beyond that tragedy, when we throw away food, we have gotten nothing in exchange for all those enteric methane emissions. We’ve gotten nothing for all the water, labor, fertilizer, fuel, and other resources used to grow that food and get it to you. This waste is compounded by the fact that most food waste winds up in a landfill. Discarded food makes up a quarter of what we put in our landfills. There, that food waste produces methane and other greenhouse gases while it decomposes. Landfill methane capture systems are not so great. About 60% of the methane produced by food rotting in landfills escapes. Yes, there’s a lot of waste in our food processing and storage and distribution system that you don’t see, and that’s another newsletter. But we are wasting a lot right in our homes and we can each do a lot about that. It’s not just about eating all our leftovers. If you have a yard, try composting what you remove in food preparation (peels, stems, eggshells, etc). If you don’t have a yard, see if you can join a composting co-op.

Bottom line: your steak is not helping the environment, and your cardiologist would like you to cut back on beef for heart-health reasons. But your steak may have a smaller environmental footprint than the food you waste. If you really want to help the planet, how about resolving to reduce your personal food waste?

The animal that does not end up buried in the landfill will thank you. And so will your children and Santa and Rudolf.

References

How food and agriculture contribute to climate change | Reuters: https://www.reuters.com/business/environment/factbox-how-food-agriculture-contribute-climate-change-2023-12-02/t

Greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture - Wikipedia

US Cattle Industry Efficiencies versus Global Cattle Industry: https://www.beefresearch.org/programs/beef-sustainability/sustainability-quick-stats/us-vs-global-in-efficiency-and-production

Cows and Climate Change | UC Davis:

https://www.ucdavis.edu/food/news/making-cattle-more-sustainable

Rennet Facts: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rennet

Genetically-Engineered Rennet Approval: "FDA Approves 1st Genetically Engineered Product for Food". Los Angeles Times. 24 March 1990. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1990-03-24-mn-681-story.html

Burping and flatulence: methane gas emissions and cows (rte.ie)

Theological Meaning of Kosher Restrictions: https://www.chabad.org/kabbalah/article_cdo/aid/2670214/jewish/Kosher-Animals-and-Humans.htm

Danish farmers required to halve greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 | Reuters https://www.reuters.com/business/sustainable-business/danish-farmers-required-halve-greenhouse-gas-emissions-by-2030-2021-10-05/

Taxing farming vital for Denmark’s climate target | Reuters: https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/taxing-farming-vital-denmarks-climate-target-govt-adviser-2023-02-20/

Euronews -- German farmers’ protest over diesel tax break cuts: https://www.euronews.com/green/2023/12/18/german-farmers-protest-over-diesel-tax-break-cuts-brings-traffic-to-a-standstill-in-berlin

Energy efficiency of meat animals: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/energy-efficiency-of-meat-and-dairy-production

Environmental Impacts of Food – Consumer Ecology: https://consumerecology.com/footprints/

Turkey Carbon Footprint & Environmental Impact - Consumer Ecology: https://consumerecology.com/turkey-carbon-footprint-environmental-impact/

Wild mammals have declined by 85% since the rise of humans, but there is a possible future where they flourish - Our World in Data: https://ourworldindata.org/wild-mammal-decline

What is the White-Tailed Deer Population by State? - A-Z Animals (a-z-animals.com)

Docket EPA-HQ-OLEM-2022-0415-0001 Regulations.gov

Comments on National Strategy for Reducing Food Loss and Waste: https://www.regulations.gov/document/EPA-HQ-OLEM-2022-0415-0001/comment

Video of cow chewing cud: https://www.bing.com/videos/riverview/relatedvideo?mid=7BD31F298F28FD12CE0E7BD31F298F28FD12CE0E&ajaxhist=0

Educational videos about cow digestion: https://www.bing.com/videos/riverview/relatedvideo?mid=B63BCA7F92248398304EB63BCA7F92248398304E&ajaxhist=0

A trip through the digestive system of a cow – Really! (The “inside story”) https://www.bing.com/videos/riverview/relatedvideo?mid=7BD31F298F28FD12CE0E7BD31F298F28FD12CE0E&ajaxhist=0

Thanks for sharing another fascinating and well-researched article, Kristin. I appreciate how you combine your farm-based personal experiences with Science and the policies of government oversight and hugely commercialized agriculture.