Not-So-Sweet Home Alabama

Show me your papers ... for everything!

Note to my readers: This post is a companion to my third post (Some Already Tried This at Home) about the role of immigration in US agriculture, focusing on Alabama, the third state to pass a law based on immigrant “attrition through enforcement.” This 2011 Alabama law went beyond the Arizona and Georgia laws in its provisions designed to keep undocumented immigrants out of the state. In this post, I go into the details of this especially harsh law, its impact on Alabama’s farmers, and how well replacing seasoned farm workers with unemployed city-slickers and prisoners worked.

Alabama began its anti-immigrant experiment in June 2011 with HB 56. This law—later designated Alabama Act 2011-535, the Beason-Hammon Alabama Taxpayer and Citizen Protection Act—was the harshest anti-immigrant bill passed by any state at that time. Kris Kobach, the indefatigable Kansan anti-immigration activist who wrote the anti-immigrant laws for Arizona (HB-2779 in 2007 and SB-1070 in 2010) and Georgia (HB 87 in 2011) also wrote this Alabama law, based on the philosophy of “attrition through enforcement.” Kobach claimed he finalized the text while on a hunting trip, sitting in his Kansas turkey blind. Somehow, shooting turkeys seems like an appropriate analogy for what happened next. Kobach believes that you only have to shoot (hopefully not literally) down a few undocumented immigrants to get the rest to self-deport. Unfortunately, his law shot quite a few Alabama farm balance sheets, leaving them bleeding red ink.

Alabama Act 2011-535 starts with the declaration that “The State of Alabama finds that illegal immigration is causing economic hardship and lawlessness in this state and that illegal immigration is encouraged when public agencies within this state provide public benefits without verifying immigration status.” The two “public benefits” explicitly named are law enforcement and public education.

Alabama Act 2011-535 pulled state and local police into immigration enforcement by requiring them to check citizenship and immigration status during any traffic stop or other encounter. They had to detain anyone who could not show proof of legal residence or citizenship until their status is verified. Local and state law enforcement had to turn any undocumented immigrants they detained in this way over to federal authorities to deport. The law made “unlawful presence” in the US an Alabama state Class C misdemeanor punishable with a fine and jail time (not more than 30 days). Working without work authorization also became a state Class C misdemeanor.

Alabama’s undocumented immigrant population was more settled in the state than that of its neighbor Georgia, which had just begun its own anti-immigration experiment in April 2011. That is, undocumented immigrants working on farms in Alabama usually reside in the state, whereas many of Georgia’s undocumented farm workers live outside the state and work their way across the state, following the harvest northward. Thus, 2011-535 included many provisions to make Alabama residency difficult for undocumented immigrants. Attempting to register a car, get a driver’s license, or maintain their homes’ connection to municipal water supplies without legal residency became a Class C felony. Mobile home registrations couldn’t be renewed without proof of US citizenship. Like Arizona’s 2010 law (SB-1070), the Alabama law makes giving an undocumented immigrant transportation to a job site a Class C misdemeanor punishable with a fine. Knowingly renting accommodations to an unauthorized immigrant and a long list of other “facilitations” including false documents became Class A misdemeanors. If ten or more immigrants are involved, it’s elevated to a Class C felony. The state would confiscate whatever vehicle you used for “facilitation.” Those false documents? $1000 fine for each. Alabama employers had to terminate employment of all undocumented immigrants, relying on E-Verify despite its known high error rate. Alabama employers intentionally employing undocumented immigrants became subject to a variety of state penalties beyond losing licenses and permits, such as fines of 10 times the wages claimed as a business expense and enhanced monitoring of their employment practices.

Any state resident could petition the state Attorney General to bring enforcement action against an employer, even without evidence of violations. If an undocumented immigrant was the victim of a crime, they had to be referred to federal government for deportation at the conclusion of legal proceedings of their case. Alabama courts would no longer enforce the terms of any contract made with an undocumented immigrant other than those made for transportation out of the state.

What happened after this Alabama law went into effect? Portions of the law became effective in the middle of Alabama’s 2011 harvest (September 1st). But even before it became effective, Latino workers with work authorizations and mixed-status families fled the state along with the undocumented workers explicitly targeted by the new law. Farmers had fewer people to harvest their crops even before the law became effective. Many high touch-labor crops like tomatoes, squash, and blueberries rotted in the field.

Recruiting non-immigrants currently on unemployment from cities like Birmingham to harvest crops did not work. Farmers reported that these recruits “very seldom make a day.” Out of fifty such recruits, just one was still working in the fields after two weeks. It wasn’t just the type of work that caused them to quit, but lack of skill and physical fitness to pick and box enough produce to earn even minimum wage. Note that a lot of produce picking and packing labor is paid on a piece-rate rather than an hourly rate. Federal law requires that the piece-rate be set so that an average skilled worker meets or exceeds the federal minimum wage ($7.25/hour) for a typical eight-hour day.

This is hard work and requires much more skill than those of you getting paid to sit in a conference room expect. Is that tomato ripe enough? How do I remove it from a vine without harming either vine or tomato? How do I get it into a box rapidly without bruising it? How do I move those boxes to a truck safely? An experienced, fit crew of four can pick and box over 250 crates of tomatoes a day, earning $150 each for the day, equivalent to an hourly rate of $18.75 per hour. One 25-person team of people recruited from inner-city unemployment rolls picked and packed 200 crates in a day—and each member of that crew got only $24 for the day at piece-rate, about $3 per hour. Hardly a living wage, and definitely no incentive for someone to go off unemployment compensation, even with transportation to the farm included. How much are you willing to pay for tomatoes at your local grocer?

Alabama also tried a prison work-release program to help harvest crops in 2011-2012. It was no more effective than their program to move people from unemployment into ag jobs. No one was willing to try the Soviet approach of emptying the schools into the fields at harvest time, so farmers lost their crops. Some farmers reported losing hundreds of thousands of dollars of produce. But the Alabama unemployment rate dropped from its summer 2011 high of 9.3% to 8.1% after the law became effective. Some people thought that was evidence that large numbers of unemployed Alabamans were taking jobs that unauthorized immigrants had previously filled. Well, not so fast. There are two ways to decrease the unemployment percentage: (1) create more jobs or (2) reduce the number of people looking for jobs. In Alabama’s case, two-thirds of the decrease in the unemployment rate was due to the workforce shrinking. Only one third of the drop came from the creation of new jobs and that rate was similar to the national trend as the economy recovered slowly from the 2007-2008 recession. Those new jobs were in the automotive sector, not in agriculture.

After losing a fortune on unharvested high-labor crops, Alabama farmers switched to lower-labor and lower-value crops the following year. Farm equipment sales associated with crops like tomatoes went down. Rural economies based on high-touch labor crops suffered. The 2012 loss to the state’s total (all-industry) real gross domestic product commonly attributed to the Alabama Taxpayer and Citizen Protection Act was $11 billion, about a 6% decline. Tax revenues fell, and not only from unauthorized immigrants, but businesses impacted by their departure. Especially interesting was the violent crime rate: it rose! Law enforcement was overwhelmed with enforcing 2011-535. They could not de-prioritize immigration enforcement to handle violent crime because of the provision that allowed anyone to sue them for not enforcing 2011-535. And, the immigrant crime victims stopped reporting crimes and assisting law enforcement, fearing deportation. So much for protecting Alabama taxpayers and citizens from crime.

Ironically, the law resulted in very bad publicity for the state when an executive of the new, job-creating Mecedes plant was arrested after a traffic stop made because his rental car’s license plate was incorrect. The German citizen was not carrying proof that he was in the US legally when he was stopped. Then a Japanese Honda executive was arrested. Some foreign-owned companies considering locating new facilities in Alabama cancelled these plans. Missouri tried to woo international investors away from Alabama by advertising that the “Show Me” state was safer than the “Show Me Your Papers” state.

Legal Alabama residents were dismayed to discover that every routine interaction with the state and public utilities required citizenship proof from everyone. Time to get a driver’s license renewed or a utility connection went from minutes to hours. Government and utility service administration costs sky rocketed. Citizens were not happy: some of the law’s most ardent supporters lost re-election bids. Mr. Kobach’s offer of a consulting contract to help the state defend the law was rejected.

The original bill required public schools to report each student’s citizenship and immigration status. If the student was the child of an unauthorized immigrant and needed English as a Second Language (ESL) instruction, the school had to report that student even if they were a US citizen. Thousands of children stopped attending public schools in Alabama, and not just undocumented immigrants. Mixed status families left, too. Documented unauthorized immigrant students had to leave Alabama’s public universities. This interrupted education will reduce the earnings potential and future tax revenue from these immigrants, wherever they end up. Fortunately, the law’s requirement for public schools to report undocumented children and US-born children of undocumented immigrants was shortly stopped by the courts. Courts eventually also overturned the requirement to carry documentation at all times, the criminalization of seeking work without authorization, and the ban on legal enforcement of contracts with undocumented immigrants.

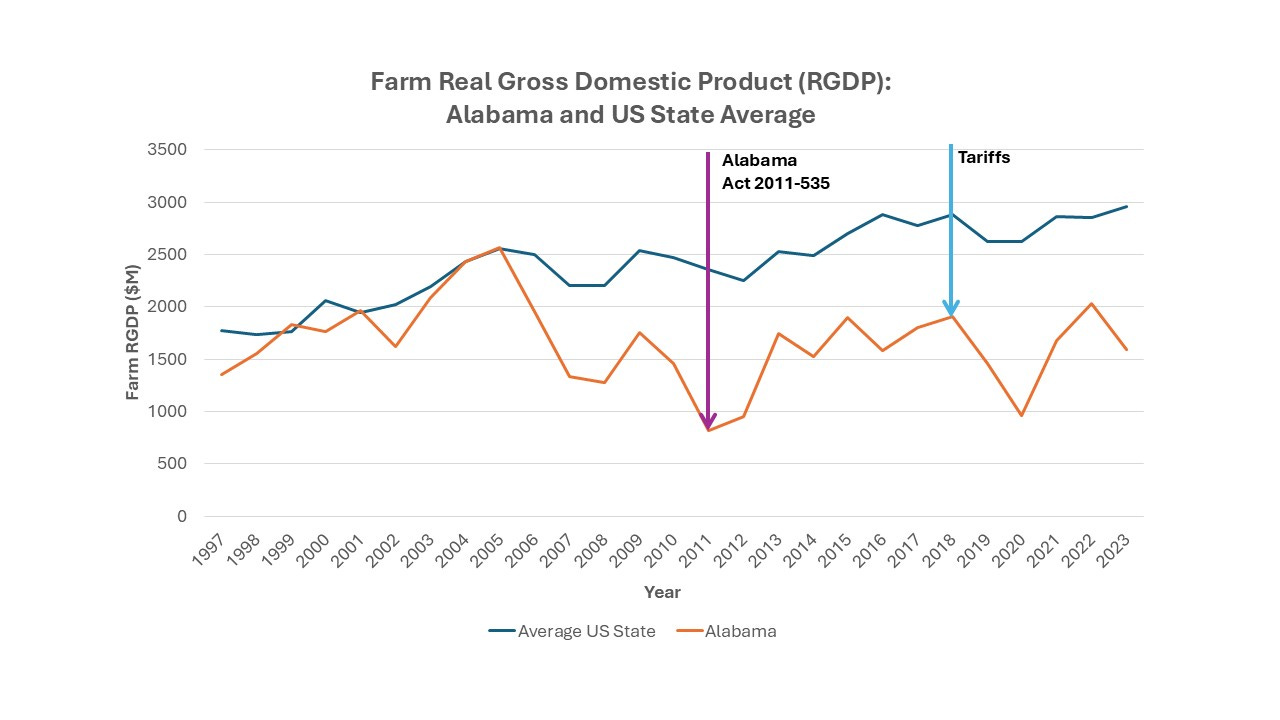

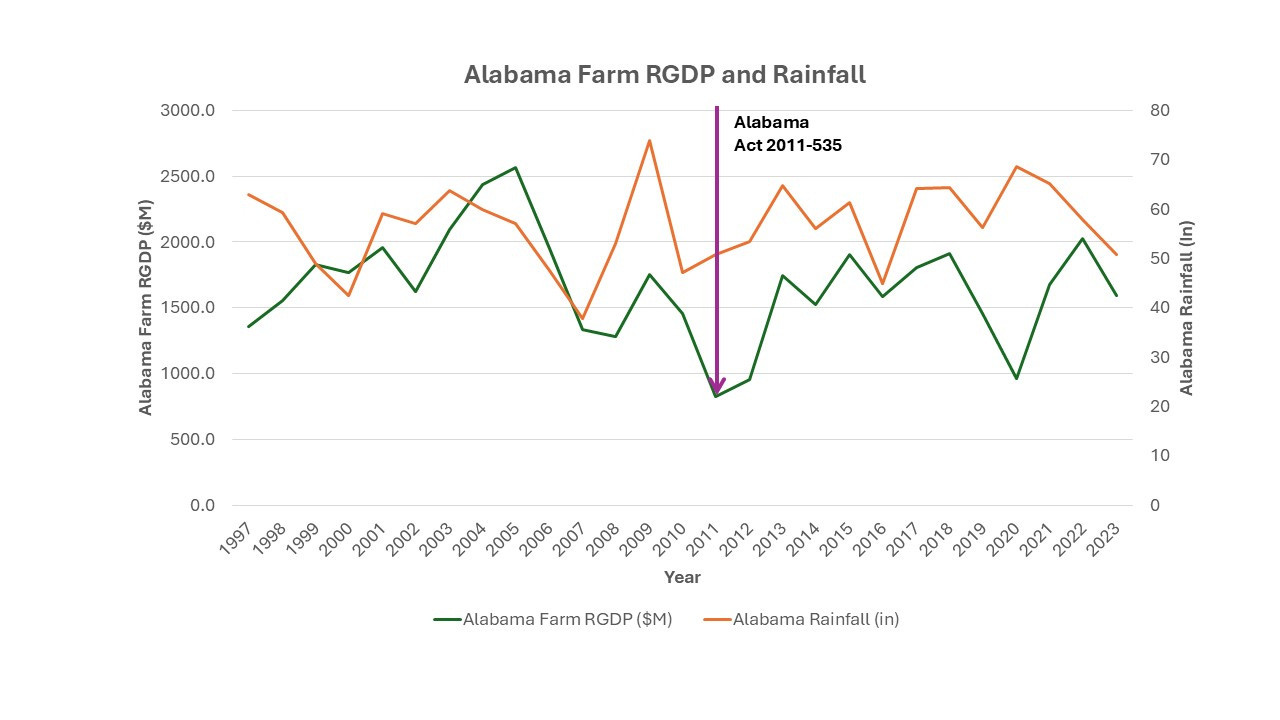

So how does this show up in Alabama’s farm Real Gross Domestic Product (RGDP)? Chart AL-1 shows that 2011 and 2012 were very bad years for Alabama farmers. But you may note, the state farm RGDP was trending down several years before the 2011 law reduced the farm workforce. There’s a 66% drop in Alabama’s farm RGDP between its 2005 peak and the 2011 trough. The rainfall (Chart AL-2) and drought indices shows that 2006-2011 were rough years, weather-wise. 2007 was the driest year since 1954, the second driest year in the 130 years with good rainfall records. 2006 and 2010 were damn dry, too. Then 2009 was the third wettest year in that 130-year period. Alabama flood damages that year topped $250M. Even the Alabama State House flooded. Year 2011 was a little shy of average rainfall, but 217 tornadoes hit Alabama in 2011, most in the spring. They caused hundreds of deaths and over $4 billion in damage, mainly in cities and towns. Yet 2011 was also a record-breaking year for tornado losses in a dozen other states, and those states’ farm RGDP did not fall. The anti-immigration law’s abrupt reduction of the harvest labor force clobbered Alabama’s farm gross income that year. Alabama’s 2011 farm RGDP was down 46% ($700M) from 2010. The state’s 2012 farm RGDP was only slightly better.

The long-term impact of 2011-535 shows up in other data. The US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Farm Census showed a very promising trend beginning in the mid-1990s toward more, smaller farms. Alabama farmers added over 11,000 new farm operations—a nearly 30% increase between 1992 and 2007—with an accompanying increase in vegetable and fruit acreage. This trend reversed sometime between 2007 and 2012, with farm operations re-consolidating to lower numbers and larger average size than the 1992 numbers by 2022. The 2022 vegetable acreage is down 67% from its peak, with 15% fewer farms growing vegetables. Fruit acreage is now only slightly over half what it was 20 years ago. Commodity acreage—cotton, wheat, corn, and soybeans—had declined from 1992 to 2007, but the acreage in these crops increased quickly by 2012. From there, it’s only gone up. It’s now higher than the 1992 numbers. Commodity crops are low labor, but you must have a lot of acres to amortize that half-million dollar combine. Once you make that purchase, you are in it for the long term. Because the overall agriculture-dedicated acreage has increased only 2% since 1992, it appears that many Alabama cattle and hog operations also converted to these commodity crops and meat poultry—just in time to be hammered by tariffs (2018) and avian flu (2021-present).

Unfortunately, the USDA farm census’ five-year interval (2002, 2007, and 2012) leaves me unable to completely separate all the effects of the anti-immigration legislation from the 2008 recession and other factors between 2007 and 2012. As a secondary factor example, over a century of intensive cotton farming badly depleted the soil and that bill is finally coming due as fertilizer costs have climbed dramatically, with one price surge coinciding with this law’s peak effect. Opening the aperture up a bit and comparing Alabama’s all-industry RGDP with that of other states shows that Alabama’s overall economic growth lags the state average significantly from 2005 onward. Its business climate is ranked 45th out of 50. So, Alabama’s precipitous 2011 farm RGDP decline can’t be blamed entirely on 2011-535, but it was the major cause.

Alabama’s farm RGDP recovered somewhat after 2012 as court cases and legislative actions removed the most draconian of the law’s provisions. But once-burned, twice-shy farmers were not rushing back to high-labor crops despite their higher market value. The huge investment in commodity crop equipment such as planters and combines also prevents a shift back. Alabama farm RGDP has averaged 12.24% lower for 2012-2023 than for 1997-2010. If we include the first (transition) year of the law—2011—in the post-2011-535 Act average (2011-2023), Alabama’s farm RGDP loss averages 15.5%.

References

From the Center for Immigration Studies: Attrition Through Enforcement

The Turkey Blind Story: Kris Kobach, the Kansas lawyer behind Alabama's immigration law - al.com

The Complete Text of the Law: Act-2011-535.pdf

Description of the Law Alabama HB 56 - Wikipedia

Repercussions of the 2011-535:

Efforts to replace immigrant workers in Alabama fields coming up short - al.com

alabama_immigration_disaster.pdf

How America's harshest immigration law failed

German Mercedes-Benz Executive Arrested Under Alabama’s Immigration Law (Updated) – ThinkProgress

US Farm Real GDP: Real Gross Domestic Product: Farms (111-112) in the United States (USFARMRGSP) | FRED | St. Louis Fed

Alabama Farm Real GDP: Real Gross Domestic Product: Farms (111-112) in Alabama (ALFARMRGSP) | FRED | St. Louis Fed

Alabama Farm Census Data from USDA NASS:

Other Relevant Data:

The 2018-2019 dip in Farm Real GDP:

Chart: U.S. Farmers Lost Billions to Trump-Era Retaliatory Tariffs | Statista

Fertilizer Costs: