Take a Detour Around Georgia

How far can YOU throw a watermelon?

Note to my readers: This post is a companion to my third post (Some Already Tried This At Home) about the role of immigration in US agriculture, focusing on Georgia, the second state to pass a law based on immigrant “attrition through enforcement.” This 2011 Georgia law was designed to keep undocumented immigrants out of the state. In this post, I go into the details of the law, its impact on Georgia’s farmers, and how well replacing seasoned farm workers with unemployed probationers worked.

Far removed from the southern US border, Georgia joined Arizona in the anti-immigrant frenzy by passing an attrition through enforcement immigration law in April 2011. Unlike in Arizona, anti-immigrant sentiments in Georgia could not be blamed on a surge of illegal crossings and violence spilling over the international border from Mexican drug cartels. Still, Georgia’s new governor—Nathan Deal—had won election by whipping up latent anti-immigrant sentiments in his 2010 campaign. Governor Deal was not a newcomer to exploiting fear of immigration. As a US Congressman, he introduced legislation into the US House in 2005 to cancel the birthright citizenship clause of the 14th Amendment of the US Constitution. Obviously, that did not pass, but in retrospect, it was a harbinger of things to come when he went home to Georgia in 2010.

Georgia’s HB 87, Illegal Immigration Reform and Enforcement Act of 2011 was based on Arizona’s SB-1070. Our friend Kris Kobach—author of the Arizona law—helped Georgia legislators write it. He slightly modified the Arizona language being challenged in court at that time. For example, instead of requiring that law officers verify legal residency, the Georgia version authorizes them to do so. It also limits requirements for employers to use E-Verify to those involved in state contracts. Georgia greatly increased penalties for undocumented immigrants using false papers to get a job. The Arizona penalty is 3 years, 9 months in prison, while the Georgia penalty became up to 15 years in prison and up to $250,000 in fines.

A large portion of the Georgia harvest workforce doesn’t live in Georgia. Rather, many workers are migratory contract labor, following harvest labor needs north from Florida through Georgia and then farther north every year. It was easy for those workers to skip their usual Georgia work stops. Even immigrants with work authorizations felt unwelcome and detoured around Georgia. Thus, this law cost Georgia about 50% of its agricultural workforce almost overnight.

Governor Deal set up a program to help farmers employ convicted criminals in probationary status. These probationers—numbering about 100,000 in 2011—had an unemployment rate around 25%. Turns out that harvesting watermelons requires a lot of skill as well as physical fitness. You must be able to quickly identify a ripe melon, separate it from the vine without damaging the vine or melon, and throw the ripe melon to a co-worker on a wagon moving through the field. The worker catching it on the wagon decides which bin the melon belongs in and gently puts it there. No one gets paid for smashing melons! Once the wagon is full, the melons must be sorted again while moving on a conveyor. Then they must be boxed, and the boxes must be loaded on trucks. The probationary felons didn’t last an entire day. At least they left with a new appreciation for farm workers! Maybe the politicians who voted for HB 87 should have tried a few days in the field—they might have left with more respect for farm workers, too.

The Georgia Agribusiness Council estimated produce crop losses starting at $140 million in the first year to $1 billion per year after that. Blueberries, blackberries, peaches, onions, cucumbers, and watermelons were abandoned in the fields. As Megan McArdle put it so well in 2011 (The Atlantic): “If workers are needed to run a farm, then zero workers is the same as zero crops, and zero farm. Some labor may be replaced with capital, but in other cases the farms might just shut down.” She’s not exactly a bleeding-heart liberal.

The US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Farm Census for Georgia—done at five-year intervals including 2007 and 2012—supports Ms. McArdle’s point about farms just shutting down. A quarter of the Georgia farms growing vegetables in 2007 had stopped by 2012. The 2012 vegetable acreage was the lowest in 20 years. The decline in high-labor crops continued after 2012. A third of the 2012 vegetable operations were gone by 2017. Total Georgia farm acreage declined, too.

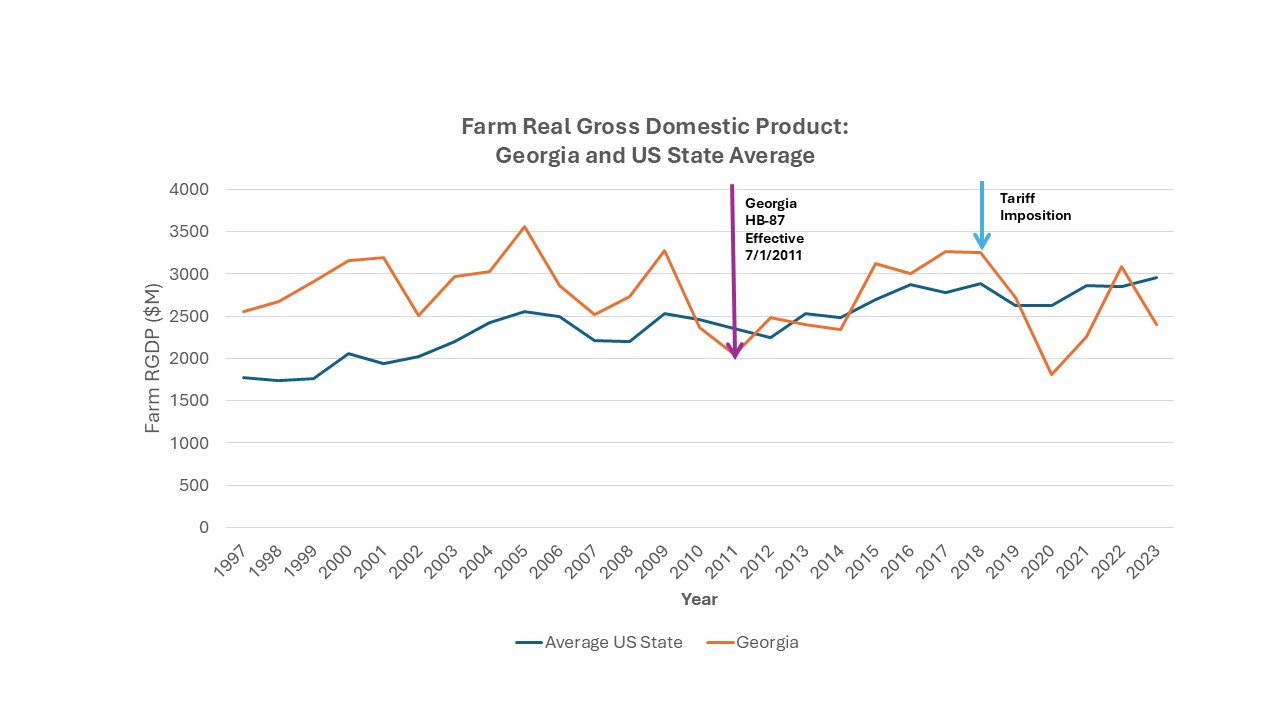

Chart GA-1 shows Georgia’s farm Real Gross Domestic Product (RGDP, or GDP adjusted for inflation). Georgia’s farm RGDP exceeded that of the US average for all states, even in the extreme drought years of 2006 and 2008, until 2010. A check of Georgia’s all-industry RGDP shows that the Great Recession began early in Georgia and ran deep, but Georgia farmers still out-performed the US state average through that general economic downturn.

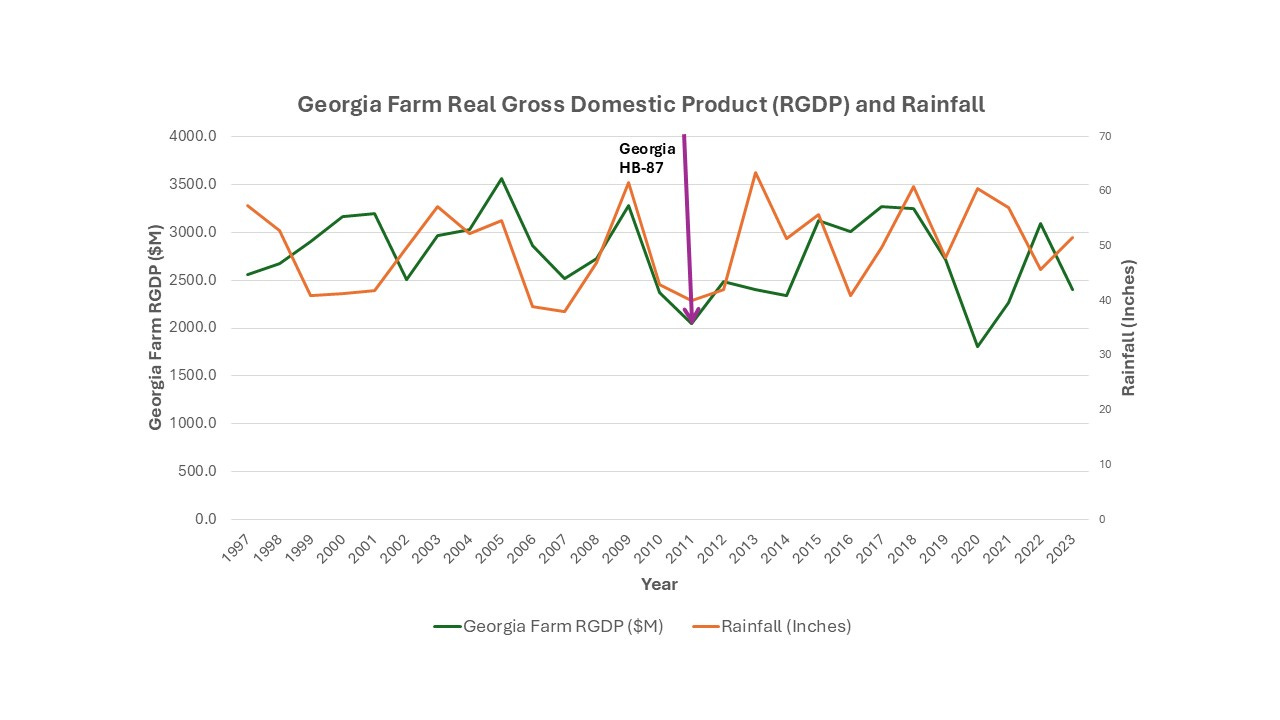

Now take a look at Chart GA-2—rainfall and farm RGDP—to make sense of Georgia farmers’ extreme challenges during this period. The years 2006-2007 brought the worst drought in fifty years. Irrigated acres increased significantly during this period, reducing the impact of rainfall on crop production. Then 2009 was the wettest year in nearly 50 years, claiming 10 lives with material destruction around $500M. The low 2010 farm RGDP was at least partially due to the flood recovery. The 2010-2012 seasons were not quite as dry as the record drought in 2006-2007, but they were really dry in Georga. Yet the farm RGDP in 2011—when HB 87 became effective—was lower than in the drier years of 2006-2007. The HB 87 labor shock in 2011 appears to have been a killing blow for many farms with a large investment in high-labor crops. The USDA Agriculture Census shows that hired farm labor costs increased about 24% between the 2007 and 2012 censuses. Contract farm labor costs (including temporary harvest help) increased about 44% in the same period.

In 2012, the Supreme Court of the US (SCOTUS) case Arizona v United States blocked many provisions of the Georgia law—including the provision that allowed police to investigate the immigration status of people who have not been arrested. Georgia vegetable acreage has rebounded since 2012, but total farm acreage did not. Some farmers just gave up completely, while others switched to lower-labor crops. The RGDP recovery in 2015 followed by the dive after 2018 shows that many Georgia farmers switched to commodity crops in the period after HB 87 became effective. Georgia commodity crops include peanuts and cotton as well as corn and beans. Peanut product exports fell by a factor of 15 after the 2018 tariff imposition.

Today’s surviving Georgia vegetable farmers (46% of the 2007 peak) now each farm more acreage, probably after investing more in machinery and joining the H-2A visa program. Machinery can cut labor costs on produce headed for processing (think tomato sauce, some bruised fruit is okay), but vegetables destined for the “fresh” market remain labor-intensive (think sliced tomatoes on your sandwich, bruises yuck). Today, the US issues over three times the number of H-2A visas as in 2010. Georgia now ranks third in the number of H-2A visas issued each year. About 67% of these seasonal guest workers work on vegetable, melon, and tree nut farms. As you will recall from an earlier post, costs of H-2A participation and compliance are considerable, favoring large operations with seasonal labor demands. I applaud Georgia farmers for employing people legally; however, the H-2A visa program has become one more force driving consolidation of farms.

Even with many provisions blocked in 2012 and the increase in H-2A visa participation, Georgia’s agriculture economy has not recovered to its prior levels. It fell from its ranking as Georgia’s number one industry prior to HB 87. The average farm RGDP for the 12 years prior to HB 87 was about $222 million dollars greater per year than the average 12 years since. Georgia’s farm RGDP has averaged 7.7% lower for 2012-2023 than for 1997-2010—despite the 1997-2010 period including five awful droughts compared to only two drought years in the 2012-2023 span.

If we include the first year of the law—2011—in the post-HB 87 average, Georgia’s farm RGDP loss is 9.4%. I had mixed feelings about including the transition year, so I’m leaving you with both calculations.

References

From the Center for Immigration Studies (CIS): Attrition Through Enforcement

Governor Deal’s Bill to Eliminate Birthright Citizens: https://www.congress.gov/bill/109th-congress/house-bill/698/

Georgia 2011 HB-56 Text: C:\pdf\116631.wpd

Georgia House Bill 87 - Wikipedia

Georgia's Harsh Immigration Law Costs Millions in Unharvested Crops - The Atlantic

The Nation: The High Cost Of Anti-Immigrant Laws : NPR

Georgia Farm RGDP: Real Gross Domestic Product: Farms (111-112) in Georgia (GAFARMRGSP) | FRED | St. Louis Fed

US Farm Real GDP: Real Gross Domestic Product: Farms (111-112) in the United States (USFARMRGSP) | FRED | St. Louis Fed

Prison Probationers Fail as Farmworkers: Ga. sends criminals to replace undocumented immigrants - POLITICO

Ga. immigrant crackdown backfires - POLITICO

Georgia Farm Census Data from USDA NASS: st13_1_001_001.pdf

Weather Impacts: Average Precipitation in Georgia by Year and https://www.drought.gov

Explaining the 2018-2019 dip in Farm Real GDP:

Chart: U.S. Farmers Lost Billions to Trump-Era Retaliatory Tariffs | Statista