Ghosts of Turkeys Past

What is the Aztec Trickster God Tezcatlipoca doing on your dinner table?

You may not be thinking of Thanksgiving turkey yet, but turkey growers are. And I am, because in my search for Farm 2.0, I have noticed a lot of poultry operations for sale. Courtesy of the Lone Star tick, I have an allergy to mammal products – Alpha-gal Syndrome – that contributed to my retirement from sheep and cattle farming (Farm 1.x). An unrelated chicken allergy has narrowed my focus to turkeys and ducks. I think I should grow food that I can taste-test and quality-test myself, leading me to wonder about these turkey farms for sale.

“Ready-made income stream,” one realtor’s ad trumpets. “Turn-key poultry operation for investment!” and “Over one hundred thousand square feet under roof, ready for birds!” and so forth. The prices are relatively good in an otherwise over-heated real estate market. Turns out that these “turn-key poultry houses” have been idle for a while. Some for quite a while. Why? Are these operations salvageable?

Unlike me, many American consumers think of turkey as a “special occasion only” protein source, where that special occasion is Thanksgiving and possibly Christmas. About 88% of Americans have turkey for Thanksgiving dinner. This tradition comes from the time when you could shoot a wild turkey nearby in the fall when it was big enough to be a large family’s dinner – about 17 pounds. Compare that to the average farm-raised turkey now: about 33 pounds!

Given our tradition biasing American turkey consumption toward holidays, Thanksgiving and Christmas comes earlier for modern turkey growers than it does for consumers. The business has something in common with sheep farming: you quickly learn to count backwards from holidays. Come March, hatcheries are working overtime and feed mills are busy mixing and filling bins. In parallel, the farmers are prepping their poultry houses for millions of young birds (called “poults”). March is the first of two peak deliveries of poults in a year. Most of these birds are destined for deep freeze, waiting for T-Day. The next peak poult delivery, usually larger, is August. The hen poults will spend about three months on a farm growing from about an eighth of a pound to over 20 pounds. These August poults are likely to become the “fresh” turkey in late November. The hen leaving the farm enroute to your Thanksgiving table will be about 130 times the size she was when she left the hatchery.

I can see the leading edge of each generation of birds when I drive by the Tyson hatchery on Holly Farms Road in Amelia County. Counting cars and trucks parked around the hatchery tells you how the poults are progressing. This Tyson Hatchery began as a Holly Farms Hatchery many decades ago, hence the name of the road. Do you remember Holly Farms? I remember it as the local “fast fried chicken” eatery in Orange, Virginia, not far from our family farm. For many years, it was the only fast- food place in the area. It was a short walk from the Farm Service Agency office when I was a kid. Before we knew about Colonel Saunders and Kentucky Fried Chicken with mashed potatoes, we were eating Holly Farms chicken with potato wedges between FSA business and farm co-op shopping. I’m not sure which my mother liked more: the chicken or those potato wedges. Both were a rare and welcome break from home-cooking. I dropped plenty of hints about both during FSA visits, because I was usually the one who had to prep and fry chicken and peel potatoes at home. Holly Farms left the skin on the potato wedges, an innovation that I worked hard to transplant to our house.

Holly Farms was one of the earliest large-scale poultry growers, possibly the first to go end-to-end, from eggs to hot food on your plate. The company was officially "founded” in 1958 in North Carolina, but its founder Fred Lovett had been in the poultry business for fifteen years by then. He started young helping his father as a middleman for eggs and poultry, getting product from small flock growers in North Carolina to regional markets. Their business grew with the increase in demand for eggs and chicken as World War 2 got underway. By the 1970s, Holly Farms was a fixture on the southeastern US fast-food scene. Prior to WW2, the typical poultry business had been a farm sideline run by the women, selling eggs and broilers for extra cash to tide the family across gaps in more seasonal mainstream crop income. In fact, the poultry business was somewhat stigmatized as “women’s work” until demands from a world war and crises such as pestilences and droughts caused mainstream crop failures. Holly Farms had been a real farm prior to its 1958 entry into poultry, but its origin in the late 19th century was in cotton and cotton compressing. Cotton-compressing was the business of baling cotton for shipping, using large hydraulic presses to reduce the unprocessed volume and thus export shipping costs. Then came the Boll Weevil. By 1987, Holly Farms had nearly $1.6 billion in sales, half in chicken, somewhat less in turkey, and absolutely nothing to do with cotton compressing. It had moved its headquarters from North Carolina to Memphis, Tennessee by then. It was the only poultry “brand” that carried the original farm name all the way to the consumer. Check out this 1986 promotion of its turkey: Dinah Shore 1986 Holly Farms Turkey Commercial - YouTube.

But Holly Farms disappeared in a hostile take-over by Tyson Foods in 1988 and 1989, with about $1.3 billion ultimately changing hands. Tyson and ConAgra fought over Holly Farms for almost a year, and one casualty of that fight was Tennessee’s laws against hostile take-overs. Tyson was the nation’s largest poultry processor then, but not by much. Its acquisition of Holly Farms nearly doubled its market share. Tyson had been primarily an institutional supplier, while Holly Farms was better known in the grocery store and on the street. Oddly, after paying this fortune partially for the name recognition, Tyson soon phased out the Holly Farms name. Only little artifacts remain, like the name of the road where that old hatchery still operates. The Holly Farms chicken place we frequented in Orange became a series of different restaurants, all local. It’s a Mexican restaurant now. Ironically, as I write this, Tyson has announced plans to bring back the Holly Farms “brand” – just as they announce cutbacks in poultry production in Virginia. I suspect that the Mexican place is not going to turn back into a chicken place. Besides, there’s now a Kentucky Fried Chicken and Taco Bell Combo less than a mile from that original Holly Farms joint. And the first McDonald’s in the region is only a few hundred yards away.

Fall in the Shenandoah Valley is still ushered in with eighteen-wheelers carrying turkeys for the Thanksgiving demand peak, whether those turkeys or processors belong to Holly Farms or Tyson or ConAgra. These trucks – lined up for miles at processing plants – leave a roadside dusting of white turkey feathers swirling in their wakes. The USDA’s Economic Research Service (ERS) says that Virginia is the sixth-largest turkey producing state. In 2021, Virginia produced 14.5 million slaughter-weight turkeys. I can only imagine what the country roads look like in October in the number one turkey-producing state. That’s Minnesota, producing 40.5 million turkeys in 2021 alone, about 19% of all the US-produced turkeys. Total US turkey production in 2021 was 216.5 million birds. This sounds like a lot of birds, but it’s actually a decline from a peak of 302.7 million in 1996.

US residents are now eating 16 pounds of turkey a year on average. This is second only to Israel in the world. The turkey processors have worked hard to convince us to eat turkey year-round. They are succeeding, somewhat. In 1970, the typical American ate half of all their turkey consumption on holidays. Now, it’s less than a third.

The whole roast turkey you put on the table for Thanksgiving is most likely a hen turkey (adult female) while the ground turkey you buy at other times of the year is most likely a tom turkey (adult male). Young males are called “jakes” and young females “jennies.” Yes, we refer to young female turkeys with the same term we use for female donkeys. It seems that “jenny” became a common moniker for the female of many species, including women, as the Spinning Jenny became associated with women’s work in the industrial revolution. The chicks are called “poults” until they are about 4 weeks old. Age and sex of the turkey have less influence on the flavor of the meat than they do with sheep. Domestic turkey does taste different from wild turkey, due to both genetic differences and diet. Diet is likely the greater influence. Domestic turkeys eat grain throughout their lives while wild turkeys eat plants and bugs early in the year and switch to seeds and acorns in the fall.

A flock of turkeys is called a “flock” in a farm poultry house, but a “rafter” when you are hunting them in the wild. It’s almost always the tom turkey displaying that beautiful fan of feathers, when he “struts” to attract hens or intimidate other toms. I’ve never seen a hen turkey strut, but an internet search will yield a few rare instances. And incidentally, only tom turkeys “drum” and “gobble.” That’s why some people call a tom turkey a “gobbler.” The gobble is the turkey’s version of a rooster’s crow. Hens “yelp.” Really. It sounds like a chihuahua’s barking. The hen uses it to find other turkeys, like “Hey, I’m here and I’m looking for turkey friends.” Both males and females “cluck” to each other when close. A turkey hen makes a special series of clucks to signal the toms that she is in the mood, a very useful bit of trivia for a turkey hunter who wants to bag a tom turkey.

The only turkeys on our Virginia farm were wild turkeys. Those wild turkeys spent most of their lives foraging in the woods. A rafter of turkeys sifting through leaves on the forest floor – looking for bugs and nuts – is almost the noisiest party you will find in the woods even if the birds don’t speak. All that churning of leaves is louder than a bunch of squirrels chattering. Only a coyote concert is louder. During over five decades there, we were trying to help restore the wild turkey, so we didn’t hunt them. The Eastern wild turkey was hunted nearly to extinction 1890 to 1930, and repopulation efforts were unsuccessful until the late 1950s. Nowadays, it’s not uncommon to see rafters of 30 or more birds in Virginia. A few days ago, I saw a trio of hens strolling along the access road of a mid-sized airport near Richmond – hardly the wilds! I think we can declare victory on wild turkey restoration.

Did you know that Ben Franklin favored making the Eastern Wild Turkey our national bird instead of the Bald Eagle? Old Ben must have spent a fair amount of time hunting and watching turkeys, developing some appreciation of their special intelligence. Of course, anyone who has seen a big wild tom turkey strut his stuff would be impressed. Check out this link: WILD TURKEY STRUT - DRUMMING, SPITTING, & DRAGGING - YouTube.

The Aztecs associated turkeys with their Trickster God Tezcatlipoca. The Trickster God was most commonly represented as a jaguar; however, this god of creation and bringer of good and evil sometimes manifested as a turkey. Other experts argue that Chalchiuhtotolin or “Precious Turkey” was actually a separate and lesser god rather than a face of the high god Tezcatlipoca. I am neither a theologian nor an anthropologist, so I won’t get into that argument. What blew my farmer-mind was learning that the Aztecs had turkeys. American turkeys were domesticated long before Columbus “landed” in the Americas. Native Americans domesticated turkeys at least 2000 years ago. Both Aztecs in what is now southern Mexico and the Anasazi in what is now the southwest US (Four Corners region) domesticated their local sub-species of wild turkey. Both cultures had already domesticated corn, which they fed their turkeys, so corn-fed turkey is not a new or unnatural way of raising turkey. Over a thousand turkeys were sold every day in a typical Aztec city market. The Aztec domesticates’ feathers were probably mostly bronze in color. The Spanish Conquistadors liked this exotic and tasty Aztec bird. They took some bloodstock back to Europe, where the bird flourished on farms. The moniker “Turkey” came into use in Europe, as the Europeans thought the birds resembled Guinea fowl from Turkey the country. The descendants of these exported birds were then imported back into the New World in 1608 to Jamestown. Their descendants are our modern commercial turkeys, with a little infusion of Eastern Wild Turkey genes along the way.

The pure white turkeys that got the Presidential pardon in November 2022 – named Chocolate and Chip – are Broad-Breasted White turkeys, the major commercially-raised US breed now. That’s why the feathers dusting our roads as Thanksgiving approaches are white. So how did modern turkeys end up white, instead of the Aztec turkey’s bronze? Or the variegated brown and bronze permanently engraved in our childhood minds along with stories of Pilgrims? Or in some dated Virginia history books, claiming that Virginians started the holiday? In elementary school, I remember dutifully turning pinecones into turkey table decorations with pipe-cleaner legs and heads and brown construction paper tail fans. Sadly, the domestic turkey’s wild Southern Mexican turkey ancestor subspecies is now extinct. Maybe it’s appropriate that its descendants are now white: our culture portrays ghosts as white and we only have DNA ghosts of those turkeys that the Aztecs domesticated.

Unfortunately, the real reason for white feathers is much more prosaic: We are less likely to notice the white pin feathers inevitably missed in cleaning the turkey. This means those of us without farm roots are less likely to freak out when we unwrap our grocery-store turkey. Because a typical domestic adult turkey has almost 3,000 feathers, some of the tiniest are going to get missed during processing.

I suppose that white feathers are attractive in the apparel industry for the same reason white wool sheep are: the white gives you more color options with dye. But there are only so many people wanting feather pillows or hats nowadays. I can’t help but wonder if someone is trying to breed a naked turkey to save the expense of plucking them and getting rid of the feathers. Turns out that domestic turkeys have only about a third the number of feathers that wild turkeys have, so the idea has occurred to some turkey geneticists. The trend toward breeding naked turkeys may have slowed due to the creation of some “secondary value streams” from feathers. I periodically see promising-sounding schemes to replace wood pulp with chicken and turkey feathers in paper and building products, but these ideas have not yet gotten widespread traction. In 2023, the main uses of turkey feathers are still composting for fertilizer and “feather meal,” a feed additive high in protein. Feathers, it turns out, are mostly keratin like your own hair and fingernails – and (of special interest to this retired sheep farmer) – wool. Feathers survive a lot. Archeologists frequently find ancient feathers. That’s how we know about the early domestication of the turkey in North America.

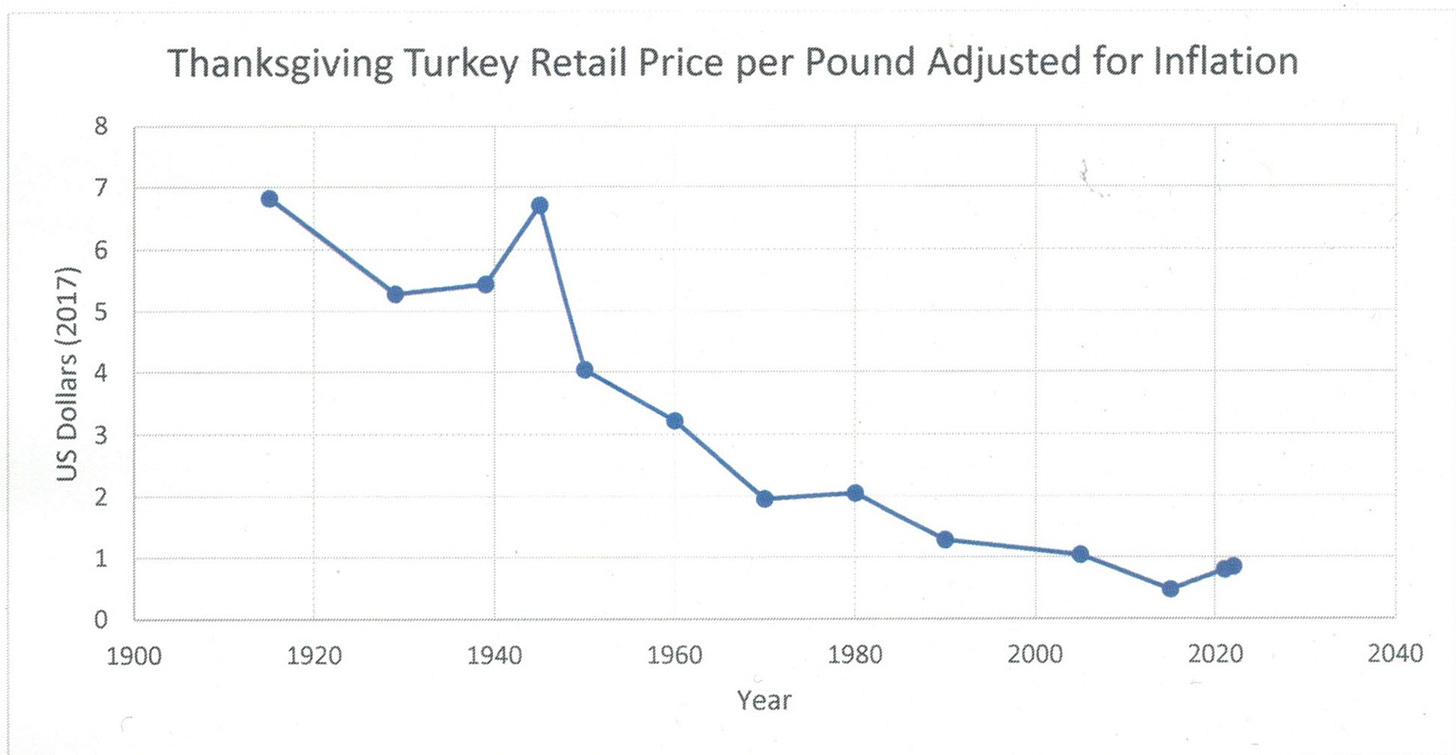

Now, what about that “Broad-Breasted” part of the Broad-Breasted White Turkey breed? Their large breasts mean lots of “white meat” (preferred by most modern Americans over “dark meat” from other turkey parts). Those huge breasts make the turkeys too heavy for their wings. Thus, they are instant lunch for coyotes in the wild. Given the opportunity, these birds tend not to rush out of the turkey houses to experience “free range” life for very good reason. The size of turkeys at slaughter are now over twice what they were in 1960 (averaging 15.1 pounds in 1960 to over 33 pounds in 2019). Furthermore, these birds are consuming less feed to get to that weight and growing to slaughter weight in about half the time that their 1960s progenitors did. These genetic improvements mean lower costs and lower environmental impacts per pound of turkey on your plate. Take a look at inflation-adjusted turkey prices at the grocery store over the last hundred years:

Your great-grands paid about 14 times as much a hundred years ago (on a per pound basis, adjusted for inflation) than you paid for your last few Thanksgiving or Christmas turkeys, even after factoring in the bird flu. The record high prices we heard about for Thanksgiving turkey last year were not really that high when viewed as part of a hundred-year trend. What about input prices paid by the farmers raising these turkeys? Fertilizer and labor prices have increased dramatically over the decades; however, the raw inputs that come from other farms have not. Take the price of feed corn (actually No. 2 Yellow) in Memphis, TN, as an example:

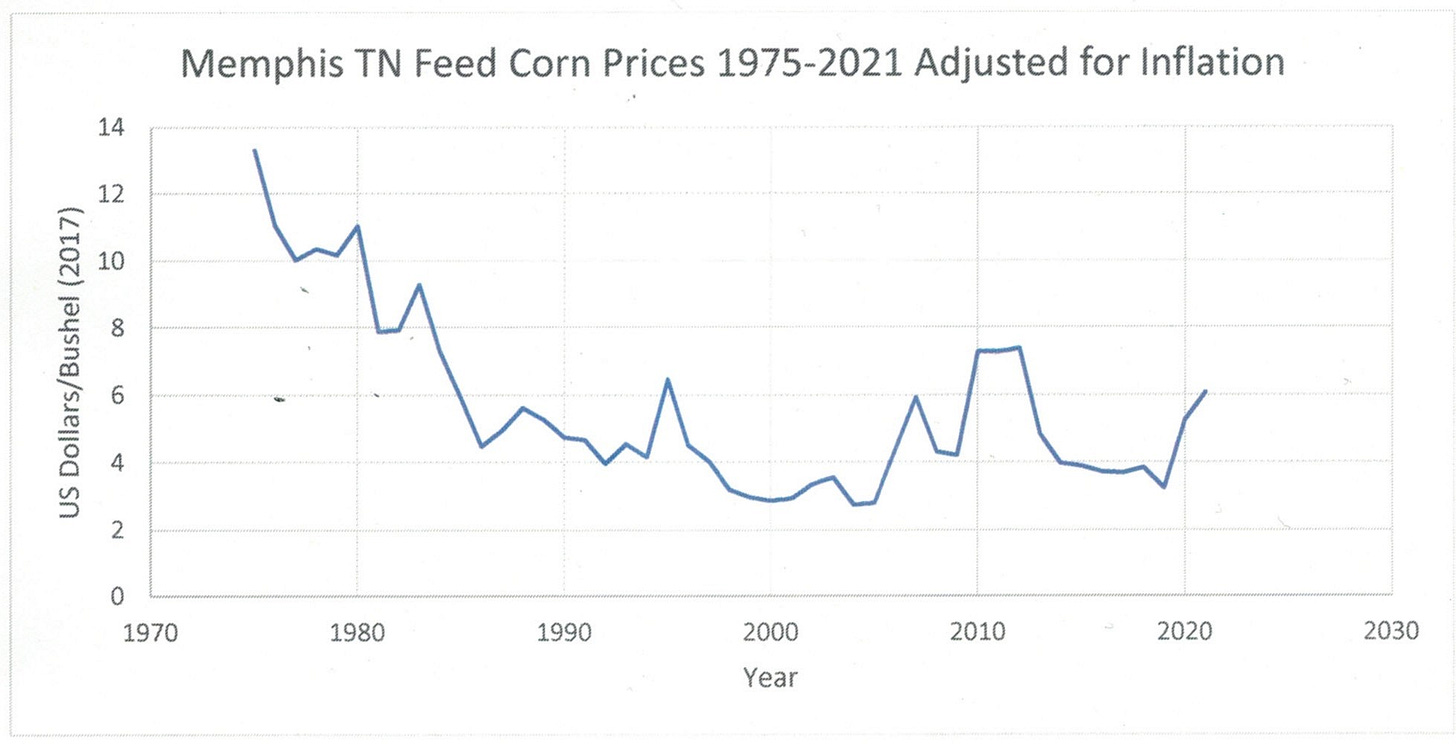

Unfortunately, this is not the price of the mixed, carefully-balanced feed that the modern turkey eats – there’s a lot of hauling and grinding and mixing in other ingredients between the corn grower and the turkey grower. Also, I don’t yet have inflation-adjusted feed corn prices all the way back to 1920; however, you can see from this 1975-2021 data that the inflation-adjusted price of corn is about one-quarter of what it was 1975. Turns out that retail turkey prices just before the pandemic were about one-quarter of what they were in 1975, too. Many genetic improvements in poultry have occurred since 1975. But inflation-adjusted fertilizer prices have tripled in that same time frame! While feed costs tend to fluctuate with fertilizer costs in the short term, genetic improvements in feed crops are helping to offset the upward trend of fertilizer and other crop inputs in the field (crop-focused newsletters are coming).

So the turkey on your Thanksgiving table or on your sandwich is much changed from its Aztec ancestor in feed conversion efficiency, size, growth rate, and feather color. None of this is “GMO,” just selectively breeding turkeys just like Gregor Mendel did with his peas. Well, almost: artificial insemination with plants is somewhat easier than it is with turkeys! But even with the Trickster God’s help, the birds have not figured out how to convert air and dirt to muscle mass while standing in the rain 24/7. In addition to feed costs, there’s steadily increasing capital, land, building construction, fuel, machinery, regulatory compliance, and labor costs that should drive turkey prices upward. At some point these “input” cost increases more than cancel the savings from genetic improvements and any government subsidies. Is this why those poultry farms are on the market? Would it be crazy to enter the turkey business now? How should this figure into your decisions in the grocery store?

Stay tuned. Our food system is complicated even without the Trickster God’s help. I’ll share my convoluted journey through these questions in a more near-future installments focusing on turkeys.

References

Alpha-gal Syndrome | Ticks | CDC

Dinah Shore 1986 Holly Farms Turkey Commercial - YouTube

Tyson Offers $1 Billion for Holly Farms - Los Angeles Times (latimes.com)

Tyson Foods, Inc. -- Company History (company-histories.com)

Broad Breasted White turkey - Wikipedia

Overview of the U. S. Turkey Industry 11/09/2007 (cornell.edu)

Meet a Turkey Farmer! | Daddy's Tractor (daddystractor.com)

Tracing the Wild Origins of the Domestic Turkey - Cool Green Science (nature.org)

History of Wild Turkey in Virginia | Virginia DWR

The Wild Turkey Zone: Wild Turkey History

https://www.worldhistory.org/Tezcatlipoca/

Recycling Poultry Feathers: More Bang for the Cluck | Greenbiz

A century of Thanksgiving grocery ads (and turkey prices) – Chicago Tribune

Corn Prices - 59 Year Historical Chart | MacroTrends

Inflation Calculator | Find US Dollar's Value from 1913-2022 (usinflationcalculator.com)

USDA ERS - Turkey Sector: Background & Statistics

Poultry - Production and Value 2022 Summary 04/27/2023 (cornell.edu)

Turkeys Are Twice as Big as They Were in 1960 - The Atlantic

Nice article, Kristin! Being a Westerner, I had never heard of "Holly Farms." But it's an interesting part of your story and a good example of the constantly-morphing landscape of our agriculture-restaurant industry. Also, I'm not sure if I've ever seen a wild turkey, but the part about toms "drumming" and crowing exactly fits what I remember the wild pheasants doing in California's Central Valley when I was a kid. This short video shows a ring-neck pheasant crowing and drumming, but it doesn't happen until the one-minute point: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O023HiF9I1U. I remember the drumming and crowing sounds being VERY loud in person.